Updated: date

Published: February 19, 2018

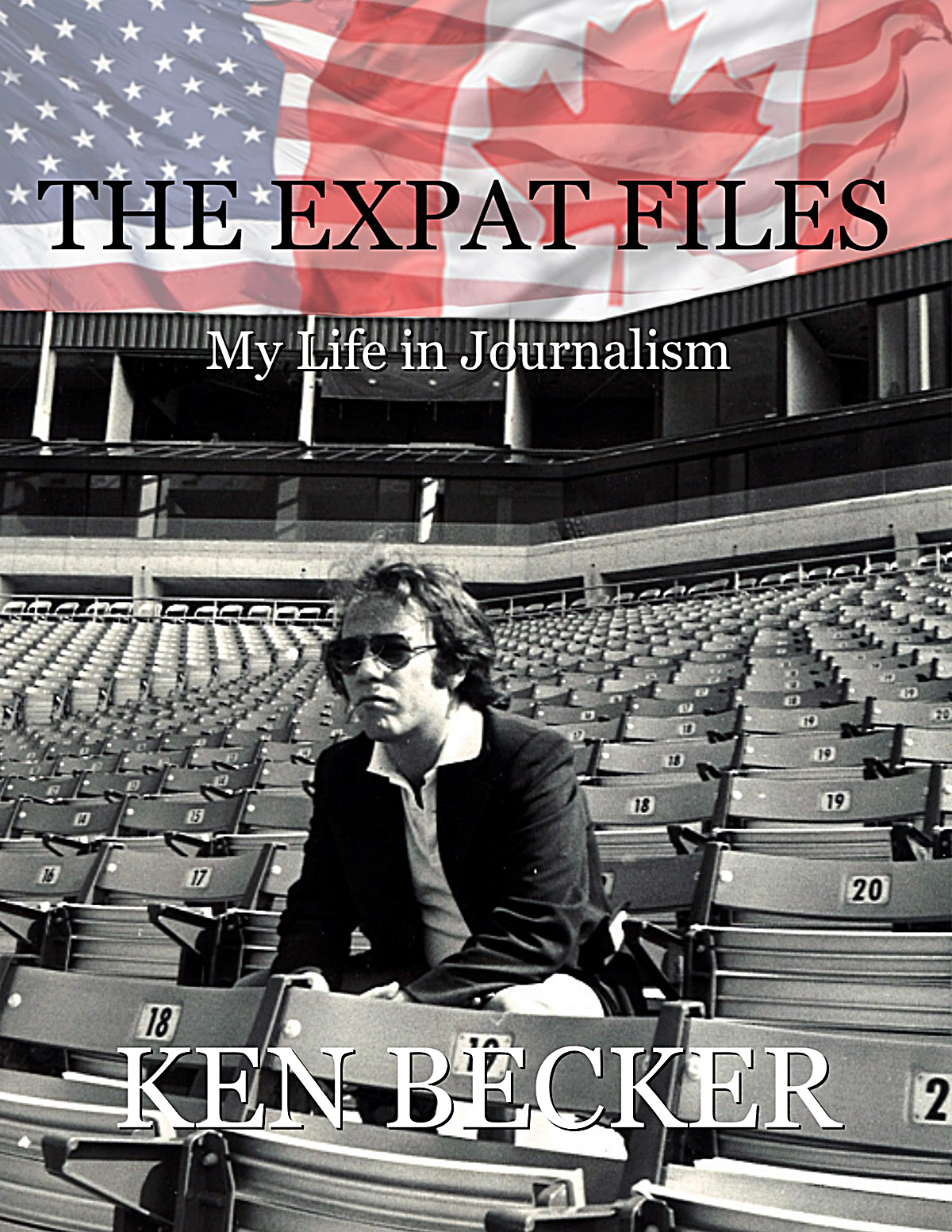

The Expat Files: My Life in Journalism

By KEN BECKER

Editor’s Note: When I heard that my former colleague Ken Becker had published a memoir of his life in journalism, I wasted no time contacting him and asking for permission to post an excerpt on BestStory.ca.

During my years as Montreal bureau chief for United Press Canada (a sister service of UPI) between 1983 and 1985, I dealt frequently with Ken, who mostly ran the day-to-day operation at our Toronto headquarters.

Ken was the principal go-to “slot man” who edited the copy that we journalists in bureaus across Canada sent to him – usually under extreme deadline pressure – before putting it out on the wire to media clients around the world.

The only thing I knew about Ken was that he was a veteran editor who didn’t talk much and worked real fast to shoot our stories out on the wire to beat the competition at Canadian Press. The extent of a typical conversation was when he answered the phone with his New York bark of “Becker”, followed by the words, “Good job, buddy!” after we had finished our brief discussion about the breaking story being edited by him.

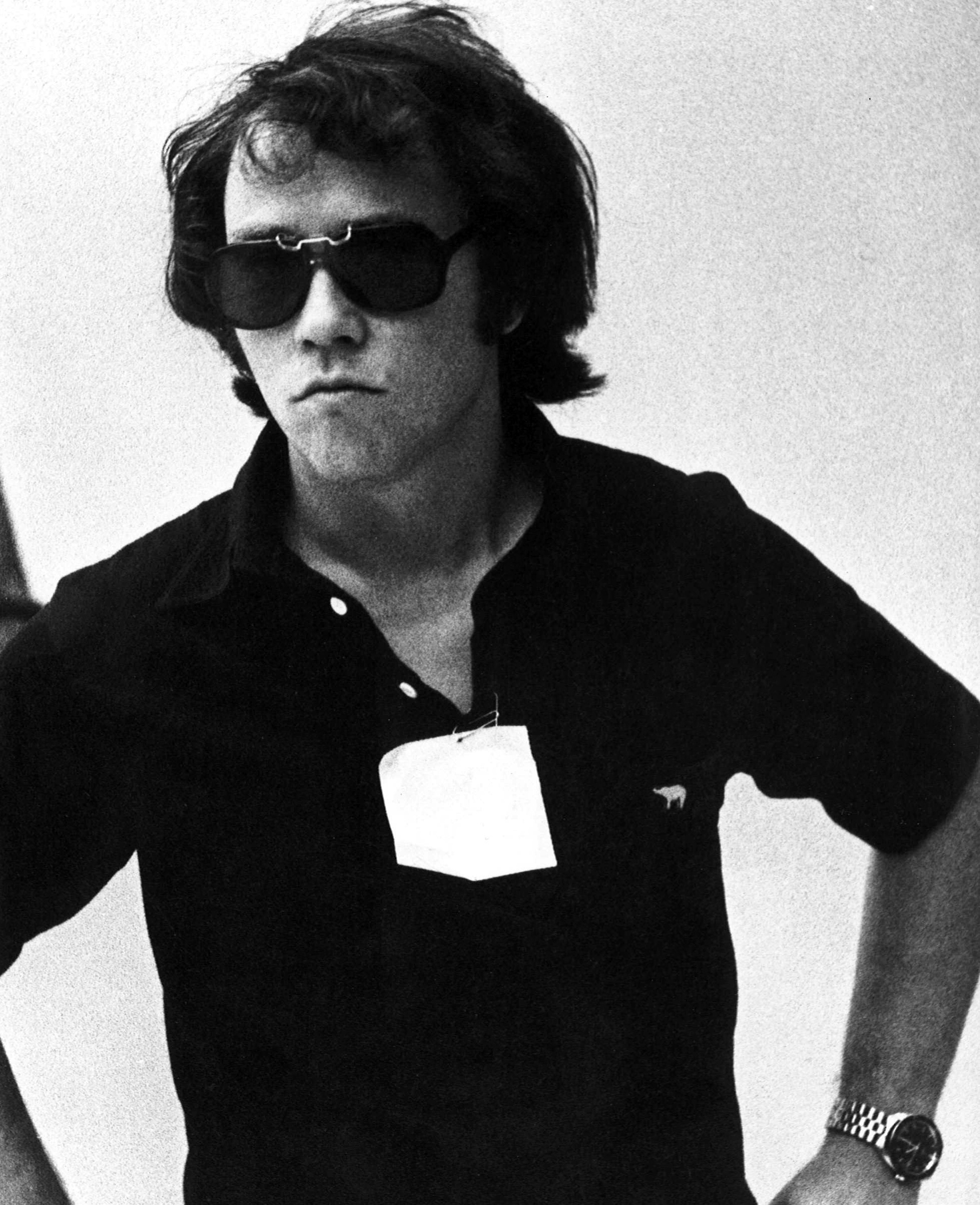

So I read with great relish all the details of his colorful career and personal life in The Expat Files: My Life in Journalism. In the book, he writes about stumbling into the news business as a 19-year-old copyboy at the New York Times in 1966 and landing his first job as a reporter at a newspaper in northern California in 1968.

He tells readers that his skills as a journalist only started to take shape in 1970 after he joined United Press International in New York under the influence of – and with – legendary editor Lucien Carr, a muse to such Beat Generation writers as Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg.

From UPI-New York, Ken was transferred to Canada at a time when he was also dealing with a split from his Swiss wife, Anita, who was living in Bern with their young daughter, Kate. After about 20 months as Vancouver correspondent, Ken moved to UPI’s Canadian headquarters in Montreal in September 1974. That’s where we pick up the story with the following exclusive excerpt from Chapter 10 of Ken Becker’s book, The ExPat Files.

— Chapter 10 —

TRICKY DICK AND TRUDEAU

On the editing desk in Montreal, doing my best Lucien Carr imitation, I handled copy from reporters in the other Canadian bureaus: Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver. I’d done some editing in New York and found it made me a better writer – seeing the flaws in the copy of others helped me spot the holes and rough patches in my own stories.

But I still craved the glory of the byline, getting out of the office and back in the street. I did get to cover a couple of front-page stories in Montreal. One involved a fugitive murderer named Richard Blass; the other the prime minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, and his wife Margaret.

I had covered Trudeau several times when I was in Vancouver. I’d jumped on his campaign plane when he came west during the 1974 election, and also went along for the ride during a state visit by King Hussein of Jordan. The king had piloted his personal jetliner to the annual air show in Abbotsford, east of Vancouver, where he and his third wife, Queen Alia, hooked up with the Trudeaus. That evening, I sat in the bar of the Hotel Vancouver with the rest of the press corps while the middle-aged king and his young wife, and the middle-aged prime minister and his young wife, were upstairs in a suite, doing god knows what.

I was focused, however, on the TV in the bar, watching Richard Nixon live from the Oval Office. “I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as president at that hour in this office.”

“Good fucking riddance, you slimy piece of shit,” I screamed at the screen. “I hope you wind up in Attica, you crypto-Nazi scumsucker – see how you like it taking it up the ass from some crazed three-hundred-pound junkie biker flying on smack.”

I’d read all of Hunter Thompson’s pieces in Rolling Stone and, if I didn’t have the freedom to write the words, I certainly could echo them in a crowded hotel bar in British Columbia.

My fellow reporters knew I was an American. I never hid it, never would, though I had been quick to lose the rougher edges of my New York accent. When confronted with anti-Americanism, I often told my Canadian friends that their only identity as a country was not being American.

I also brought to Canada a First Amendment attitude that the press was free to stick its nose into just about anybody’s business, especially those in power. That’s what led to my confrontation with Trudeau in the fall of 1974.

I was in the bureau when one of our reporters in Ottawa called with a tip that Margaret Trudeau was in the psychiatric wing of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, and that her husband was on his way to visit her.

I had witnessed Margaret on the campaign trail that summer, doing her best Nellie Forbush imitation. I’m in love, I’m in love, I’m in love, I’m in love, I’m in love with a wonderful guy. It was kind of sweet and sickening at the same time, this twenty-something standing at the podium in some small-town hockey arena asking people to vote for her man.

Personally, I found it a bit creepy that this good-looking young woman – younger than me – was sleeping with a guy my father’s age. Their first two sons – Justin and Sacha – had been born on Christmas Day, twice giving the politician a nice front-page story on a slow news day.

I had covered Trudeau enough that he knew me. During the campaign, he would good-naturedly tease me about my habit of wearing my glasses on top of my head. So, when he arrived at the Royal Victoria Hospital with his two-man security detail – they stayed in the car – he knew the one guy waiting for him was a reporter.

“What are you doing here?” he snapped.

“How’s your wife doing?” I responded.

“How would that be your business?”

“You’re here and not working. That’s the country’s business.”

He offered one of his best harrumphs, followed by a shrug of dismissal, all shoulders and arms and hands, palms up, as if to say, You’re not worth acknowledging.

I followed him into the hospital lobby. “If you’re here and not in Ottawa, you’re not doing the country’s business. The job the people pay you to do. The people have a right to know how you spend their time.”

“Fuck off,” the prime minister of Canada said.

“Is your wife seeing a psychiatrist?” My best comeback. He was approaching a bank of elevators. I kept pace. “How can you make important decisions when you have other things on your mind. Maybe you should step down until your wife’s better. Don’t you think the public has a right to know what’s going on?”

This may have been the post-Watergate period in the United States, where the press was puffed up with its own importance and not taking any crap from politicians. But Canadians did things differently, tended to believe public figures were entitled to their private lives.

Trudeau disappeared in an elevator. I retreated to the street.

His two security guys were leaning against their plain blue sedan. The RCMP didn’t constantly shield the prime minister in the same way the Secret Service did the U.S. president. I’d seen these two Mounties before and they seemed to know me. One gave me a wink. The other a nod.

I found a payphone. Called the desk and filed a bulletin advisory on the UPI wire, alerting all media that Trudeau was at the hospital. This was my reply to Trudeau’s arrogance and expletive. I’d make sure every reporter and camera crew in Montreal got to the hospital before the prime minister could slip away, that he’d be forced to run the gauntlet when he left.

Two hours later, as was often the case, Trudeau surprised me. He and his wife emerged from the hospital and went for a little stroll while reporters shouted questions and cameras clicked and whirred.

Then he surprised me again. He guided Margaret to a scenic spot on the sidewalk, a lovely backdrop of just-turning leaves on a perfect Indian summer day, and nodded toward his wife, indicating she was ready to take questions.

How are you feeling? a radio reporter asked.

“I’ve been in the hospital for the past ten days,” she said in nearly a whisper, “under psychiatric care for severe emotional stress.”

What do you ask next? Did you suffer a breakdown? How nuts are you?

She looked very pale and seriously stoned. The prime minister had offered up a sedated and wounded kitten. Any question we’d ask would seem like blood dripping from the mouth of a jackal.

“I think I’m all right and on my way to recovery,” Margaret added. “Thank you all for your concern and I hope you’ll leave me alone for a while.”

When the microphones moved toward the prime minister, he snapped, “it’s her press conference,” before the Mounties moved in, on cue, and escorted the couple back into the hospital.

I had to hand it to Trudeau. Trapped in the hospital, he’d figured out an exit strategy that would leave him smelling like the rose he always wore in his lapel.

Poor Margaret, suffering the stress of public life. Poor Pierre, all alone to run a country and a home with two little boys. That’s the impression that would be formed that day, and it would stick for a while, even as their marriage came apart. I would be back on Maggie’s trail a few years later, after she partied with the Rolling Stones and ran away from home.

Montreal was a pretty good news town. Though it was being surpassed by Toronto as Canada’s most populous city and financial center, it was the capital of organized crime, Italian Mafia and French gangs. Which provided the other big story for me in Montreal.

Richard Blass was the most-wanted man in Canada. He was known as The Cat, because he had survived several shootouts with police and fellow gangsters, once getting out of a burning hotel room after being shot four times. He’d escaped from prison – twice. The media were counting his lives and the number was approaching nine.

At about 2 a.m. on January 21, 1975, I was awakened by a call from UPI-Montreal photo chief Gary Bartlett, who told me to get up, get a cab and meet him at a topless joint called the Gargantua on the north side of the city.

“I’ve already been to a bar tonight,” I said. “Now, I need some sleep.”

“Well, this bar is on fire,” he said, “and we hear there are lots of bodies inside.”

Montreal is not the most comfortable place to be on assignment in the middle of the night in January. When I arrived, it looked like a scene from the Ice Age, icy stalagmites rising from the pavement, frozen solid in seconds as water sprouted from fire hoses. The ruins of the building were still smoldering, the now familiar scent of roasted human flesh – after covering that airline crash at JFK – spicing the wind-chill. The spinning lights of police cars and ambulances added an eerie glow to the scene. As I stood there with my notebook and fast-frozen pen, the body bags kept coming out.

A couple of hours earlier, shortly after midnight, the bar manager, a waitress and eleven patrons had been in the Gargantua when a gunman – or gunmen – entered.

The manager was shot on the spot. The waitress and the rest were herded into a six-foot by eight-foot cold-storage room, and locked inside. A jukebox was pushed in front of the door to ensure their imprisonment. Then, the place was set afire. The bar manager died of the gunshot wound, the other twelve of asphyxiation.

Back in the office, I banged out a lead comparing the Gargantua to the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre – worse, since thirteen were dead in Montreal and a measly seven in Chicago in 1929 – playing to UPI clients in the United States.

Later in the day, I added that police suspected Blass, who had busted out of prison three months earlier and implicated in a double-murder in the same bar.

After his escape, Blass taunted the cops by sending them photos of himself and “press releases” to the media, bragging he’d never be caught. That was enough to put Montreal’s most feared and accomplished detective, Sergeant Albert Lisacek, on the case.

Lisacek had the reputation as a shoot-first-ask-questions-later cop who hated bad guys and loved the media – the tabloids called him Kojak, because he looked like the Telly Savalas television character, a big man and a sharp dresser, with a shaved head.

I used to run into him in the convenience store off the lobby of my apartment building, where he once walked in on a robbery, drew his gun, scared off the lowlife, chased him into the street and shot him dead.

Lisacek was the natural choice to hunt down Richard Blass – which he did, three days after the Gargantua massacre. He and his cohorts, armed with submachine guns, found Blass in a cabin in the Laurentian Mountains, busted down the door at 4 a.m. and shot Blass twenty-three times, just to make sure he was out of lives. I wasn’t at the scene, but wrote the story, with the lead: Kojak killed the Cat this morning.

The cops never proved Blass was responsible for the Gargantua massacre. The case was written off as many other murders were in the city in those days, as a reglement des comptes, an underworld settling of accounts, a synonym for that wonderful French phrase laissez faire, which, roughly translated, means: the hell with work, let’s go to lunch.

Though I enjoyed such walks on the wild side of Montreal, there weren’t enough of them to keep my juices flowing. And I wasn’t getting enough time off the desk.

I decided the only way to get out of the office was to carve a niche for myself. With the 1976 Montreal Olympics coming, sports seemed to be the ticket.

I had already been writing stories about the serious construction delays on the main Olympic stadium and other venues. The labor unions in Quebec had a reputation for being confrontational and greedy. Both traits were coming into play on Olympic projects. Costs kept climbing as construction slowed down, all of which was big news in Canada and elsewhere.

Also, UPI needed better coverage of the city’s two big league teams, baseball’s Expos and hockey’s Canadiens. Without a fulltime sportswriter in Canada, the games were left to stringers, journalistic hobbyists who were mainly interested in a free pass to the press box. They were not capable of covering big events or writing features.

I volunteered to take on the chore. My colleagues in the sports department in New York were all for it and, with their support, UPI signed off on the new position of a fulltime Canadian sportswriter based in Montreal. Me.

I had a lifetime of experience following sports, from early childhood in New York with three baseball teams, my Brooklyn Dodgers, the rival New York Giants and hated Yankees. I’d been a passionate fan of the New York’s football Giants of Frank Gifford and Y.A. Tittle, the basketball Knicks with Walt Frazier, Willis Reed and Bill Bradley, and even the hockey Rangers of the Andy Bathgate era.

But my first love was baseball, going to games with my dad, once a star pitcher for his high school team and a legend on the city’s sandlots. Before I was ten years old I’d seen Joe DiMaggio at Yankee Stadium, Willie Mays at the Polo Grounds, and Jackie Robinson at Ebbets Field.

But I never wanted to be a sportswriter. Too much serious stuff to report. My only sports-related assignment at UPI in New York had been covering Jackie Robinson’s funeral.

On October 27, 1972 I went to Riverside Church in Manhattan. It was a perfect fall day. World Series weather. Bright sun, just a hint of a chill.

Ten days before he died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-three, Robinson, his hair white, nearly blind, had thrown out the ceremonial first pitch in the first game of the World Series between the audacious Oakland A’s and the slugging Cincinnati Reds.

The celebrity mourners gathered that Friday morning in their Sunday suits, mostly middle-aged men looking like they were attending a banquet for an old-timers game.

I spotted Pee Wee Reese, the former Dodger captain from Kentucky who had befriended Robinson early on and helped him through the storm of breaking baseball’s color barrier. Reese was standing outside the grand entrance to the church, being interviewed by Howard Cosell.

Roger Kahn, who chronicled Robinson’s struggle in The Boys of Summer, was nearby, chatting quietly with another of Robinson’s old teammates, Don Newcombe.

My press pass got me inside this VIP enclave, which was roped off and guarded by the NYPD. I was working, though my duties were uncertain.

I would not be the main man on the story. That would be the sports editor, Milt Richman. I was there to cover any “news” angles, though I was not sure what they might be. In this crowd, though, I felt more like a young fan – which I was.

A church office had been converted into a reception area. I went inside and wandered among my heroes.

There’s Hank Aaron!

There’s Willie Mays!

I wanted to go up to these guys and talk to them. But I really had nothing to say, nothing appropriate for this moment or any other. So I stood and gawked until it was time to file into the church.

The crowd, maybe three-thousand people, filled every pew. By happenstance, I sat next to Will Grimsley, AP’s lead sportswriter, a large, florid man who introduced himself then sat scrawling notes on a large writing tablet. He picked up his pace when a young black preacher delivered the eulogy, his booming voice and theatrical style mesmerizing the crowd.

“In his last dash, Jackie stole home,” said Reverend Jesse Jackson, pausing, before picking up speed, as if he was making the play. “Pain, misery and travail have lost. Jackie is saved. His enemies can leave him alone. His body will rest, but his spirit and his mind and his impact are perpetual, and as affixed to human progress as are the stars in the heavens, the shine in the sun and the glow of the moon.”

It was a hard act to follow. And nobody did. As the widow, Rachel Robinson, and her family filed out behind the coffin, we all stood. Grimsley stretched and looked around the church.

He tapped me on the shoulder. “See that guy over there, that’s Bill Veeck,” Grimsley said, pointing to a man in baggy chinos and a ragged gray sweatshirt, standing alone in the back, sobbing into a handkerchief.

Veeck was known mainly as an outlaw team owner in Cleveland, St. Louis and Chicago, famous for such stunts as sending a midget up to bat – to draw a walk. But he had also signed the American League’s first black player, Larry Doby, in 1947, and the next year gave Negro League star Satchel Page a chance to pitch in the majors.

Grimsley wandered off to talk to Veeck, while I went to find Richman and get my orders. “I want you to go to the cemetery,” the sports editor instructed. “I’ve arranged space for you in one of the cars in the funeral procession. Call me when you can with notes and quotes.”

I got into a car with a bunch of reporters and took a window seat in the back. We followed the hearse, taking the long, slow route to the cemetery in Brooklyn.

I’d heard that some schools in Harlem would be closing early so teachers and kids could line the procession route. But I was astonished at how many people turned out, at how universal was their respect for Jackie Robinson.

These were tough times in Harlem and the city’s other black neighborhoods. Black-on-black crime, fed by drugs, was endemic, as was black rage at white society.

But none of that was evident as the hearse passed. Children in school uniforms stood at attention. Women sat on stoops. Old men leaned against lamp posts and wept. It was the same scene in Brooklyn, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood.

By the time we reached Cypress Hills Cemetery, it was near dusk. The weather had changed. Dark clouds moved in as the pallbearers, Jackie’s former teammates, Reese, Newcombe, Jim Gilliam and Ralph Branca – Doby and the basketball star Bill Russell – carried the coffin to the gravesite.

I stood beside a tree, apart from the scene, added some notes to the ones I’d jotted down during the drive, found a phone near the cemetery gate and called Richman before catching a ride back to Manhattan.

I was thinking about that scene when I went to find Duke Snider on Opening Day of the 1975 season at Jarry Park in Montreal. I’d seen Snider at the church for Robinson’s funeral, standing alone, aloof, as he’d always appeared on the ballfield.

Snider had been my childhood favorite, probably because of the competition we kids imagined among New York’s three centerfielders: Mickey Mantle of the Yankees, Mays of the Giants and Snider for my team, the Dodgers. I knew I drew the short straw with The Duke, but that did not diminish my adoration. He had been a great player, a prodigious power hitter and graceful fielder, though never the equal of Mays or Mantle.

As a newly minted UPI sportswriter in Montreal, I figured I’d do some kind of feature on Snider, who joined the Dodgers the same year as Robinson, 1947, and stood by his teammate and fellow southern Californian against the rampant racism of the baseball world at the time.

Snider was a broadcaster with the Expos, who sometimes coached the players. I found him in the concrete bunker that served as the team’s clubhouse in the little makeshift ballpark.

“Hi Duke,” I said, introducing myself. “Got a minute to talk?”

”What about?”

“Well, I was just thinking that we were both at Jackie’s funeral.”

“So?”

My boyhood idol was looking down at me like I was a cockroach that had scurried into his living room. He stood there, insolent for no reason I could imagine, shuffling his stockinged feet, baseball pants rising to a belt I couldn’t see, somewhere below the huge gut that strained his white undershirt.

“Well,” I finally said, “I just thought you might like to talk about the old days in Brooklyn, Boys of Summer and all that. I grew up in New York, watching you play at Ebbets Field. Maybe we could talk about what it was like in those days, with you in Brooklyn, Mickey in the Bronx and Willie at the Polo Grounds.”

Now he looked at me as if I’d taken a dump on his spikes. “That’s old news, kid,” he said, turning to walk away, “I got work to do here.”

I thought later that he was probably right, that there was no story in talking about the Brooklyn Dodgers, long gone and forgotten by many. I had approached Snider as a fan, not a journalist. I should have asked about the Expos batters he was tutoring, kids like Gary Carter and Larry Parrish, and then maybe steered him back in time. Who of the guys you played with does Carter remind you of?

But I hadn’t prepared, just showed up like a kid looking for an autograph, thinking my baseball knowledge from the 1950s was enough to form a bond.

I’d yet to learn that you don’t – don’t want to – befriend the people you write about. Nor did I know yet that athletes were among the most narcissistic stars in the universe.

I stuck around Jarry Park that April day to watch the home opener. In the press box, the temperature was announced as eleven degrees Celsius – whatever that is – the Expos lost, and I wrote the game story.

But, after that, I left most of the day-to-day coverage of the Expos and the other Montreal teams to stringers. I was busy enough with the bozos planning to stage the 1976 Olympics.

My stories on the boondoggle of the Olympic project were getting great play in newspapers across North America and around the world. One, published in the New York Times – again with my byline stripped off – began:

MONTREAL (UPI) – What was the biggest snowbank in the city last month is now the biggest mud puddle. In a few months it even could resemble the site of the 1976 Summer Olympic Games.

It concluded with a line describing “the stadium site a circular series of blocks resembling England’s Stonehenge.”

I was starting to hear the tone I was seeking, knowing that sports could be written more from a point of view than news. Yet, writing for a wire service, you needed to please hundreds of masters.

First, I had to get my stories through an editor in Montreal, then through an editor in New York, then entice editors from Maine to Hawaii, from Newfoundland to British Columbia, to put my story in their papers.

One ex-Unipresser, Walter Cronkite, said the best way to approach a story is as if you’re writing for a Kansas City milkman, the idea being that if you can interest him, you can interest everyone in the United States.

But I wanted a sharper edge. Since I was writing sports, I turned to Red Smith of the Times for inspiration. Smith was nearly seventy and was still getting a smooth, steady flow. Sometimes he’d write with a hammer, sometimes a feather. He could wield both in the same column.

I didn’t try to imitate Smith, but thought that if I read enough of his stuff, something would rub off. It didn’t. Better stick to what I can do. Maybe it would help writing under another name, which is what I was doing as a sportswriter. I changed my byline to Ken Becker, the name I’d gone by since about age six.

While I grew up a baseball guy – and to a lesser extent a football or basketball guy – hockey was the biggest story in Canada. That’s why I covered Montreal Canadiens’ home games in the 1975 playoffs.

For me, the scene in the dressing room after each game at the Montreal Forum was better theater than the play on the ice. Not being educated in the post-game interview, I had trouble understanding why the reporters were asking players about what had just transpired. Didn’t they watch the game?

On my first visit to the Canadiens’ locker room, I found it especially comical that all the Anglo reporters gravitated to goaltender Ken Dryden, the self-anointed hockey scholar and lawyer – the Cornell grad had a law degree from McGill University – who would offer an erudite, English-only critique of the night’s proceedings.

Instead of exploring the Zen of Ken, I watched the French-speaking reporters gathered around Yvan Cournoyer. I didn’t understand what they were saying, but the Q&A seemed serious. Perhaps they were discussing nuclear disarmament, or the difference between Brie and Camembert.

The scene of English reporters only talking to English players and French reporters only to French players was the picture Canadian writer Hugh MacLennan had painted in his novel Two Solitudes, the reality of a Quebec society where French and English lived together, though always apart.

It was something I recognized in my single solitude in Montreal, living in an English enclave near the Forum, speaking only English to the clerk in the English bookstore, to the barman in the Irish pub down the street, to the waiters in the upscale restaurants I frequented, to the people in my office and the other reporters from the English media.

I had a bonjour-au revoir-s’il vous plait-merci vocabulary, just enough to be polite to the Quebecois, who were starting to get restless during my time in Montreal.

I didn’t need another language to do my work. It never occurred to me to learn French.

I was starting to get that itch again, not satisfied with what I was doing. I was eager to again write in the first-person, to cut through the bullshit with a more personal take on a story, to get a clean narrative going.

I felt my writing was in a funk, had stopped getting better. I wasn’t getting a lot of satisfaction from the sports beat, or from UPI either.

When I referred to Bobby Hull, the hockey player, as the “Blond Bomber” in a story, the sports desk in New York sent a message that read: don’t kno who “blond bomber” is – psbly a roller derby star – but bobby hull the “golden jet.”

I replied: Roller derby, hockey, wot’s the dif?

I hated making such mistakes. But I didn’t give a shit about Bobby Hull’s nickname. My body clock seemed to be telling me to move every two years, and that I had outlived my stay in Montreal.

I was bored with both my work and the city, where I mainly hung out in the press club in the Mount Royal Hotel, where I’d sometimes see Mordecai Richler holding court at the bar, or a group of hockey luminaries, sportswriters and sportscasters, reminiscing about the 1955 Rocket Richard riot.

I often sat commiserating with my news editor, Dale Morsch – Emil Sveilis, the guy who coaxed me to Canada, had left to set up a bureau in Leningrad – who drank a lot to fight depression and only got more depressed.

I knew I was a constant contributor to Morsch’s misery, since my instinct was to question authority, not respect it. But I guess I couldn’t help myself. Nor could I stop my catting around.

I was sleeping with a Jewish woman from Long Island who was working with me in UPI’s Montreal bureau. But I was also carrying on long-distance relationships with a woman in Vancouver and another in Boston, sneaking off to meet them for more intimate interplay.

At the same time, Anita and I were talking about getting back together. I’m not sure why, other than missing my daughter.

The first summer after I moved to Canada, I flew from Vancouver to Europe for a vacation in France with Anita and Kate.

In Paris, we were invited to spend a sunny day at a private swimming club where most of the women, adhering to the fashion of the time, paraded topless. During a poolside lunch of salade nicoise, complemented by a bottle of Pouilly-Fuisse, a club functionary scolded us for allowing five-year-old Kate to appear au natural.

When Anita translated the complaint for me, I went full-Yankee berserk on the Parisian prick. “You mean I have to look at these old ladies with their wrinkled, saggy tits, but you have a problem with a naked little girl?”

That set off a shouting match in two languages, with neither combatant understanding the other. I got in the last word when I raised a wine glass and threatened to smash it on the pool deck. “In America, we have the good sense to use plastic glasses outside.”

Anita and our host, her friend Willy from Bern, a banker in Paris, did not come to the defense of the gauche American and did not put up a fuss when we were asked to leave.

From Paris, Anita and I and Kate drove south, stopping to see the sights in Avignon, Arles and the Comargue before following the Mediterranean coast, bound for Nice.

At the wheel, in the dark, on the windy road atop the cliffs running down to the sea, I opened a bottle of duty-free Dewar’s and slugged it as far as Saint-Tropez, where I found a road that led to a beach and a dock.

We polished off the scotch and snoozed on the beach until dawn, when an elderly gent who looked like Ari Onassis appeared with his manservant, who told us to scram. Propriete privee!

Ari and his majordomo climbed aboard a cabin cruiser that had not been visible in the dark. We went back up to the road, stopped at a public beach – no sand, all rocks, of course – and doused our hangovers with a long soak in the salty sea.

The next night, having crossed the border into Italy, at a large seaside hotel in Ventimiglia, Anita and I had an epic brawl. This time, I smashed a glass – against a wall. We didn’t exchange a civil word the rest of my vacation. I returned to Vancouver with a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape and a tale of fear and loathing in Ventimiglia.

The next year, in the fall, I went back to Europe. But this time I traveled alone with Kate.

Anita’s father, Hermann, let me borrow his second car, a Citroen Deux Chevaux, an ugly little beast that rattled and wheezed from Bern across the Alps, into Italy.

We drove past the beautiful Lago Maggiore and on to Verona and Venice. Kate was only six, but she never complained about our wanderings in the back streets of Venice, or my prolonged stop admiring Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin in an off-the-beaten-track Franciscan church. She seemed happy with the reward of chasing pigeons while I smoked and drank in the Piazza San Marco.

By the time we got to Florence, however, she was bored – we said hi to David, raced through the Uffizi in about four minutes, hightailed it for the Mediterranean coast, and checked into the Grand Hotel in Viareggio.

These were the days when an American or Canadian could travel like royalty in Europe, when one dollar – U.S. and Canadian were about at par – bought four Swiss francs, five French francs and eighteen billion Italian lire. My first Omega Seamaster cost about fifty bucks in Bern.

At the Grand Hotel, Kate and I spent the night at the bar. The bartender took a shine to Kate – she was a charming child – and kept the Shirley Temples coming while her old man ventured from Campari and soda to scotch. We probably ate dinner as well.

In the morning, we walked on the beach but it was a cold October day and we didn’t get far. After more than a week on the road, the ugly little Deux Chevaux chugged back over the Alps to Switzerland.

As I mentioned, by the next summer, in 1975, after nearly three years apart, Anita and I were talking about getting back together. Kate was having a hard time in Switzerland, especially at school. A smart, precocious kid in New York was ostracized in Bern for not being a native and not speaking Swiss-German well enough.

Anita started to sound a little hesitant – and a lot weirder – as plans for a reunion got serious. Then, one day, on the phone, she told me she wasn’t coming to Canada. She had joined the Children of God, and her future was in the hands of Jesus.

As soon as I got off the phone, I decided Anita could join the Manson Family for all I cared – we were done – but she wasn’t surrendering my daughter to some cult.

I booked a flight to Switzerland. I talked to a colleague at UPI in Washington, who connected me with an official at the State Department.

“Do I have the right to take my daughter, a U.S. citizen, out of Switzerland, back to North America, against her mother’s wishes, if need be?” I asked.

“You mean kidnap her?”

“If you want to call it that.”

“The short answer is – no.”

But the more we talked, the more he understood the circumstances, the more sympathetic he became, the more eager to help. It was implicit that our conversation was off the record, on the QT. Even post-Watergate, there was a kinship between the press and people in government.

Finally, he advised that if I got Kate cleanly out of Switzerland, he would arrange a “safe house” – yeah, he used that term – across the border in West Germany. He gave me a name and a phone number to call at the U.S. embassy in Bonn once I got across the border.

I phoned my parents to tell them what was happening. They had been aware Anita and I might reconcile. My mother called my sister Janice and the next thing I knew her fiancé, Steven, was coming along as “muscle” on my kidnap caper.

Steven Sherman was, like my sister, a painter. But he also played the streetwise New Yorker, the Dead End Kid with a degree in fine arts. He met me at the Swissair ticket counter at Montreal’s Dorval Airport and we boarded a night flight to Zurich.

At Kloten Airport, I rented a car and drove the familiar hour-and-a-half route to Bern. We stocked up on snacks and drinks, bought a pair of cheap binoculars, and took up a reconnaissance position on a bank of the Aare, with a clear view of Anita’s parents’ house on Altenbergstrasse on the other side of the river. She was living in the same upper-floor rooms where we had bunked on my first visit.

We watched and waited. Waited and watched. Patience was never my strong suit. “Let’s take a drive past the house,” I said.

We climbed the hill, to the street where the rental car was parked. I drove around the block and crossed the little bridge over the river to Altenbergstrasse.

As we approached the house, on the narrow street, about a half-dozen hippies were walking in the opposite direction. I spotted Anita among them. And Kate. “Daddy!” she cried.

So much for the snatch and the clean getaway. I slammed on the brakes. Leaped from the car. Kate jumped into my arms. The cultists encircled us.

Steven, my muscle, tussled with a couple of guys. I took Kate into her grandparents’ house. For the first time, Hermann and Elsa Schlumpf – Anita married me for my name and kept it – seemed happy to see me.

Kate and I went upstairs to her room. Anita, Steven and the cultists followed. Shoving and shouting ensued.

The cops came. Steven and I and the cultists – the ringleader was an American – were taken to the stationhouse. Anita was suddenly at my side – and on my side. So was her father, who powwowed with the polizei.

Hermann Schlumpf was a short, wiry, solid man who, Anita told me, looked like the actor Glenn Ford. He did. He was a career civil servant who had been in the army during the war, safeguarding the Swiss border from German invasion and keeping it secure for the importation of Nazi plunder.

Hermann seemed to know the cops involved and got us sprung quickly. He also managed to get Anita’s passport back from the Grifters of God, who were ordered by the cops to stay away from the Schlumpf household. They had been crashing in Anita’s apartment and been in the process of looting her bank accounts.

Steven flew home and I stayed in Bern long enough to find a lawyer and have Anita sign an agreement that said she would lose custody of Kate if she took up with any more predatory Jesus freaks or other crazies.

Anita seemed okay. But you never know. Being married to someone doesn’t make her any less a stranger.

For the moment, everything appeared settled. I told Anita I’d take care of a legal separation agreement and the divorce. She seemed relieved and grateful.

I went back to Montreal. When an opening came up to take over UPI’s Toronto bureau, I jumped at it. Maybe another change of cities would be the answer.

In September 1975, I got back on a train and headed west.

---

How a young man who couldn't type and couldn't spell became a journalist.