Updated: date

Published: SEPTEMBER 2024

The Dingbat calendar: saga of a cultural icon

How a savvy businessman and a bohemian artist joined forces to promote a Golden Age of pharmaceutical R&D in Canada

By WARREN PERLEY

Writing from Montreal

Author’s Note: An enormous thank-you to graphic designer Karen Boor who did double duty for the better part of one year researching archives to uncover fascinating, buried facts that have brought to life the amazing stories of the men behind the Dingbat calendars.

This is the story of how two early 20th century immigrants to Canada – one an American with entrepreneurial fire in his belly and the other an artistic, bohemian scalawag from England – collaborated to promote ground-breaking medicines researched and developed in Montreal for Canadian patients.

The year was 1914 and the First World War had broken out in Europe on July 28, one month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, during a state visit to Sarajevo Serbia. Known as The Great War, it created a chain reaction of inflation, economic instability, and fear around the globe.

The Canadian government imposed price controls and rationing to stabilize a faltering war economy. It issued a call for volunteers to form the First Contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force in support of Great Britain, which entered the war on August 4, 1914 following Germany’s invasion of Belgium. The First Canadian Contingent that sailed to England in October 1914 counted 30,000 volunteers. In total, 630,000 Canadians ended up enlisting for military service between 1914 and 1918, with 424,000 of them going overseas to fight as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Canada had a population of under 8 million people at that time.

Over 30 nations declared war. The Allies included Russia, France, Serbia, Italy, Japan, the U.S.A., Great Britain and its dominion countries including Canada. They fought against the Central Powers that included Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire.

But even the dire circumstances of a world war could not douse the optimism of entrepreneur Charles E. Frosst, who had plunked down $5,000 (Cdn) to open a pharmaceutical factory in Montreal 15 years earlier in 1899. That was nine years after he arrived from his Virginia home as a 23-year-old salesman for Wampole & Co., an American vitamin manufacturer.

As a salesman with Wampole, Frosst travelled across Canada developing a network of medical sales contacts that included a close relationship with McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine. The business relationships that he developed through Wampole led him to take a leap of faith and incorporate Charles E. Frosst & Co. in Montreal in 1899.

Right from the get-go, Frosst envisaged setting up a Montreal laboratory to research and manufacture original medicines made in Canada for Canadians. He invested in hiring scientists to perform R&D. His motto was: ‘Frosst, since 1899 the symbol of progress in pharmaceutical research.’

Always his own best marketer, Charles E. Frosst wrote the advertising copy for his pharmaceutical products. His first laboratory was a modest, 2,000 s.f. plant (232 square meters) on what was then known as Dufferin Square located on Dorchester Boulevard, a major east-west downtown Montreal artery.

[Editor’s Note: In 1984, Complexe Guy Favreau, a 12-storey, four-building complex with government offices, was built on the 6-acre (2.4-hectare) plot of land that had been Dufferin Square. In 1987, Dorchester Boulevard was renamed René Lévesque Boulevard.]

One of Frosst’s earliest ads read: ‘When you specify Frosst for pharmaceuticals, you support Canadian industry and receive right quality for right prices.’ He was known to board the train in Montreal early on Monday mornings so as to arrive by 8:30 a.m. for his first visit of the day to the offices of doctors, dentists, pharmacists, and hospitals across Quebec and Ontario.

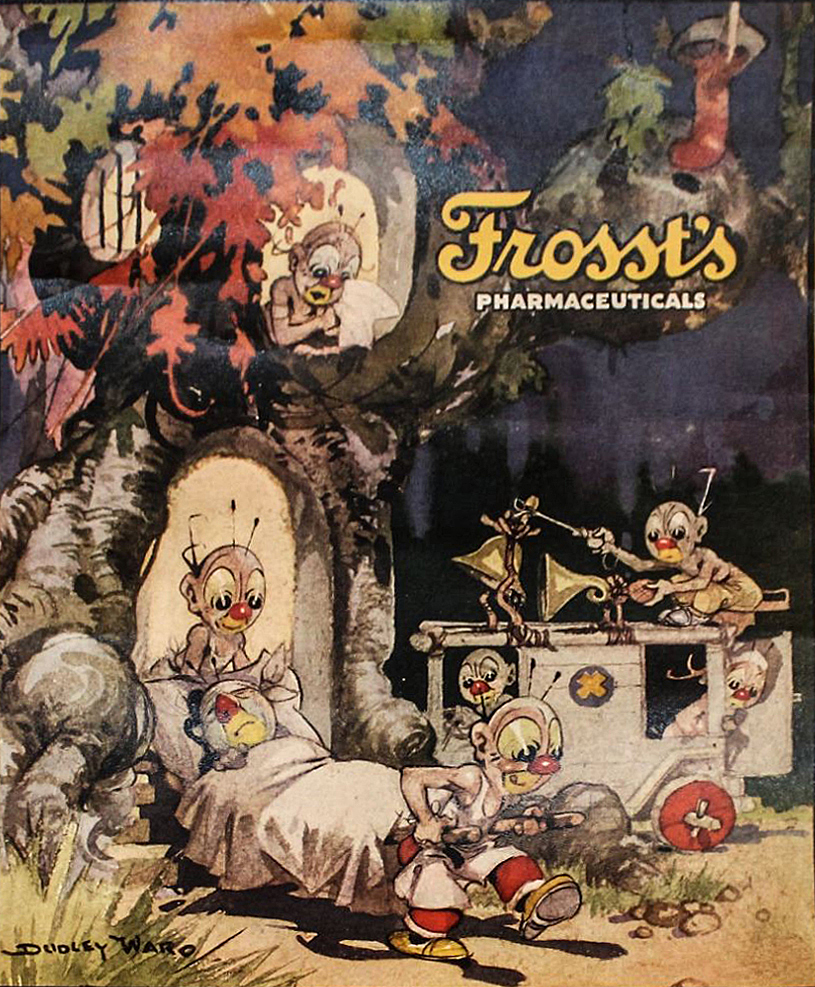

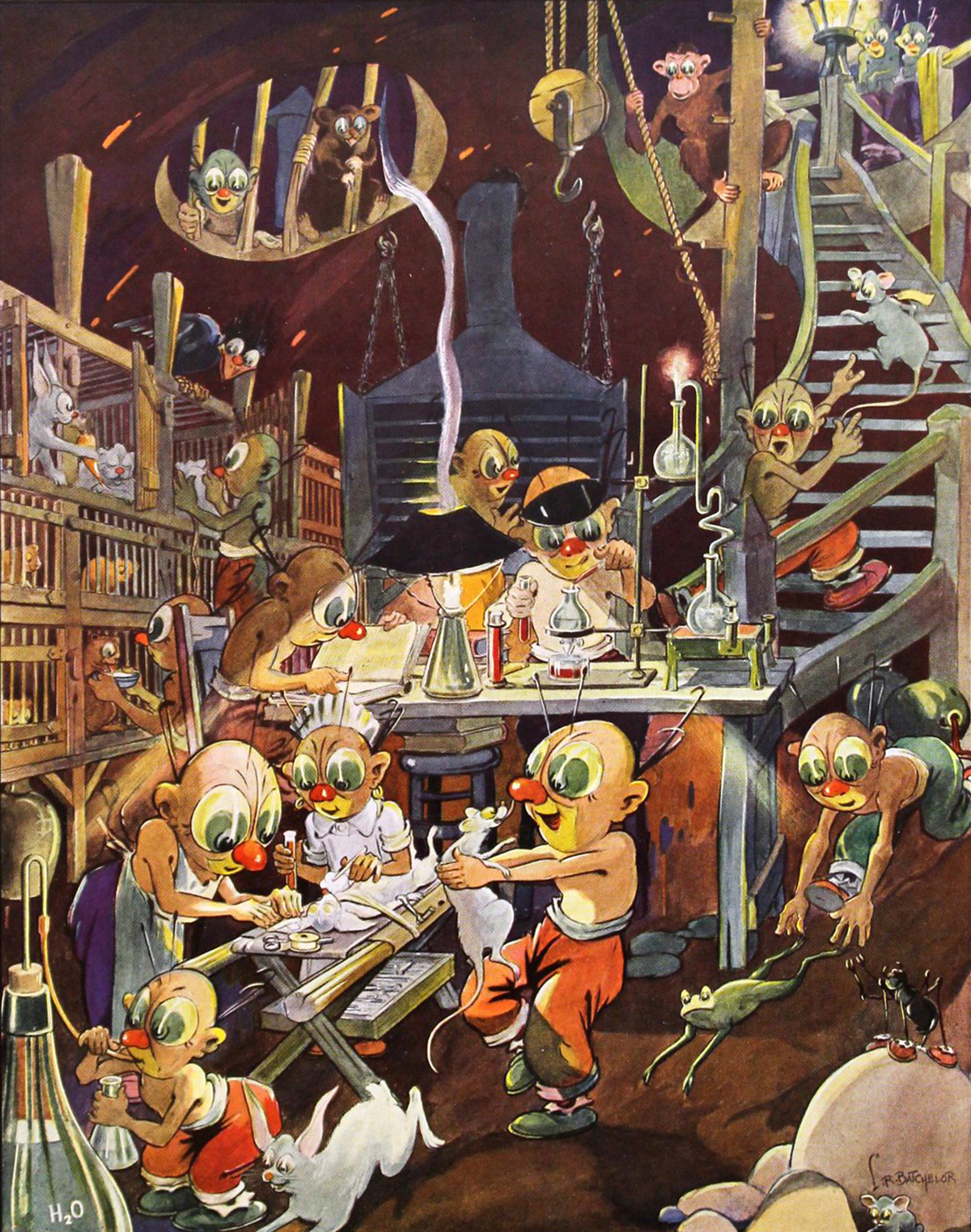

With the economic uncertainties of the First World War casting a pall, Charles E. Frosst likely concluded that a healthy injection of marketing vitality was needed to help spark sales of his medicines. The question was what form should this new marketing initiative take? His Eureka moment undoubtedly occurred when Frosst came across a watercolour painting of mischievous, little gnome-like figures called Dingbats created by artist William Dudley Burnett Ward.

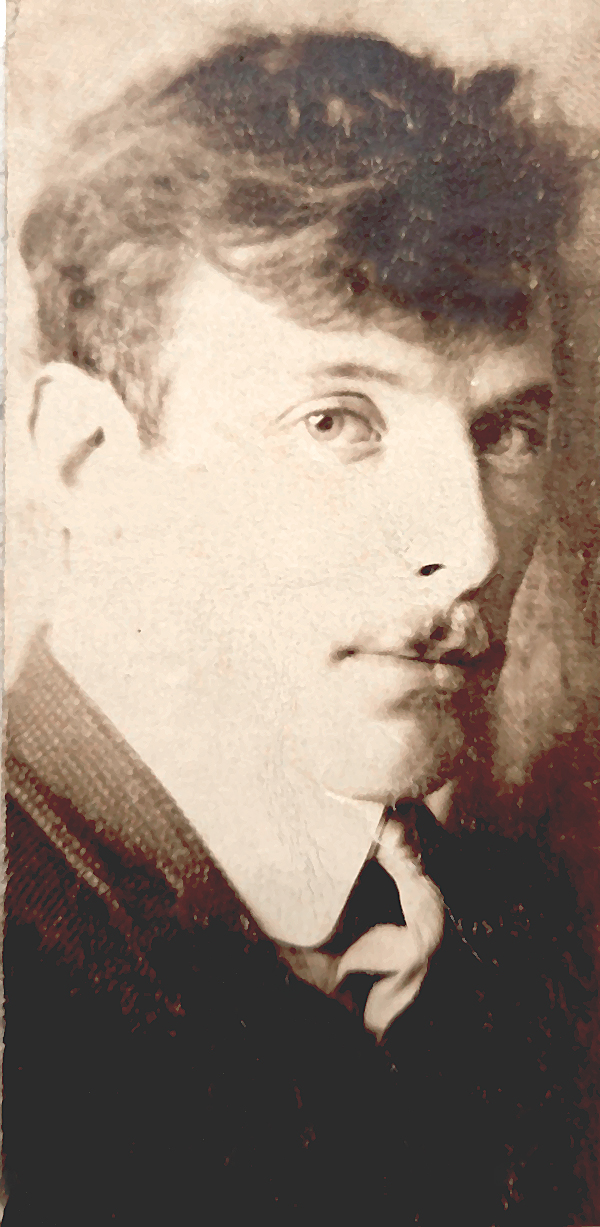

Dudley Ward, a supremely gifted artist from Staffordshire, England, had arrived as an immigrant to Canada just four years earlier in 1910 at age 31. His paintings became well known in Quebec and Ontario through local exhibitions.

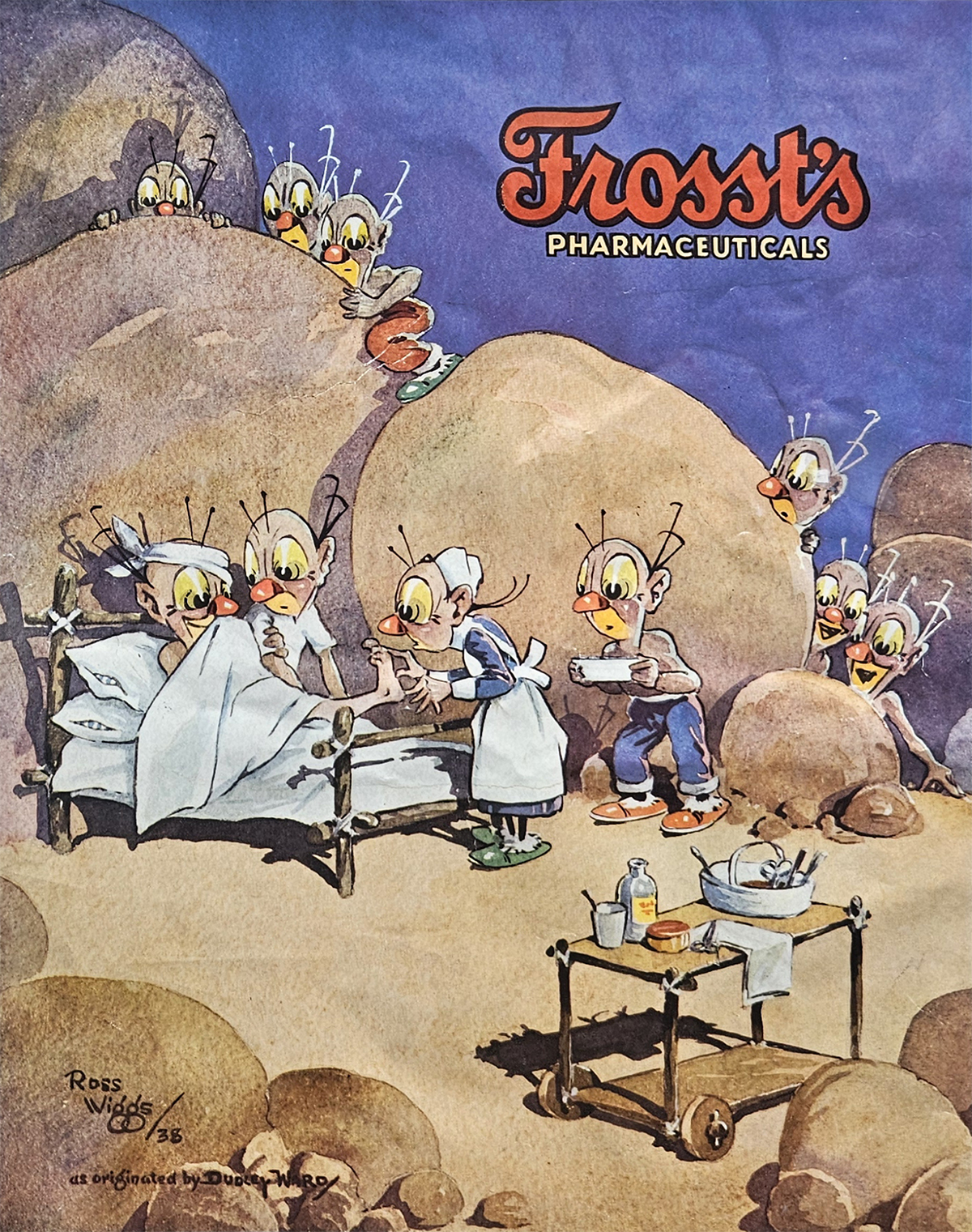

So now in the summer or early fall of 1914, Frosst reached out to Dudley Ward with his idea for a promotional calendar featuring Ward’s fantastical little creatures called ‘Dingbats’ in humorous scenes depicting science and medicine. Ward had begun using the Dingbat characters in his paintings at least six years before he created his first Dingbat calendar for Frosst. And he continued using them in paintings throughout his career, even while he produced artwork for Frosst’s annual calendars between 1915 and 1935.

The original odd couple

Thus was born a relationship between Frosst and Ward that lasted until Ward’s death from stomach cancer on February 24, 1935. Following Ward’s death, Frosst and/or his sons hired a succession of four illustrators with the imperative to copy Ward’s style, injecting the Dingbats into a different calendar scene every year – always whimsical and humorous.

The calendars started in the month of February each year and ended in January the following year. They became an iconic, cherished keepsake for pharmacists, scientists, doctors, dentists and hospitals across Canada. New Dingbat calendars were hung on pharmacy and medical office walls almost every year until they were discontinued after 1993.

[Editor’s Note: There is no known complete collection of Dingbat calendars covering every year between 1915 and 1993 – meaning that calendar publication skipped certain years due to unforeseen circumstances that might have included material shortages during the two world wars.]

Pharmaceutical industry professionals were enthusiastic Dingbat fans throughout the 20th century. In an article published in December 1985 in the Canadian Pharmacists Journal, pharmacist David Tam wrote: “People collect the Dingbat calendars for their artistic appeal and attractiveness, as well as for the gregarious charm of the Dingbat characters. The Dingbats have a sense of honesty spanning from head to toe and this adds to their magnetism.”

The Dingbat calendar tradition even survived the sudden death of Charles E. Frosst on March 18, 1948: his sons continued to distribute the calendars across Canada every year thereafter. Even after the business was bought over by U.S.-based Merck & Co. Inc. in 1965 and became known as Merck Frosst Canada Inc., the annual Dingbat calendars continued to be produced under the Frosst branding for another 28 years until 1993.

Always the consummate marketer, Frosst had understood when he commissioned Dudley Ward to create the first Dingbat calendar for 1915 that he could use part of the calendar grid to promote pharmaceutical products developed and manufactured by his company.

Among the variety of products that the company manufactured were: ephedrine, a central nervous system stimulant used to prevent low blood pressure during anesthesia; acetophen tablets, a non-opioid analgesic; vitamin and mineral supplements including iron pills; topical antimicrobial ointment; mineral oil; a glycoside compound to treat arrhythmias; atropine sulphate eye drops to dilate the pupil before an eye exam; tanning gel; and a laxative.

One of Charles E. Frosst & Company’s best-known products was the 217 painkiller developed in 1910. It combined acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) with caffeine to treat headaches and muscle pain. It was called a ‘217’ because it was the 217th item listed in the tablet section of the company catalogue. One year later, the stronger 222 painkiller containing 7.5 mg of codeine was introduced. Eventually the even stronger 292 with 30 mg of codeine was brought to market. Both the 222 and the 292 were considered narcotic analgesics due to their codeine content and were available only by prescription.

[Editor’s Note: Vintage packaging for Frosst painkillers still sell online as collectibles, but the 217, 222, and 292 painkiller medications have not been manufactured or marketed in Canada for many decades.]

While the First World War undoubtedly created new business challenges for Frosst, including production of the Dingbat calendar, it was also a very personal experience. His eldest son, Eliot, volunteered to fight overseas with the Canadian military.

The Armistice of Compiègne was signed on November 11, 1918 in a railway carriage in France bringing WW I hostilities to a close. The toll was terrible for both sides: 8.8 million military personnel and 6.6 million civilians dead. After the war ended, Eliot Frosst joined his dad in the family business with his two brothers, John and Charles Jr., also coming aboard.

By 1927, a rapidly growing Charles E. Frosst & Co. was listed in the Canadian Medical Directory as a “chemist and chemical company in Canada and Newfoundland”. It dealt in wholesale drugs, as well as supplies to hospitals, physicians, and surgeons. The company had also developed drugs to fight bacterial infections and was well on its way to becoming Canada’s leading pharmaceutical manufacturer.

They supplied medications to dentists, as well. In January 1950, the company announced a two-year fellowship to cover the operating costs of a new dental clinic for expectant mothers at the Women’s Pavilion of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. The Montreal Daily Star reported the story in its edition of January 12, 1950.

In an online profile of Charles E. Frosst, Library and Archives Canada states that one of Frosst’s major pharmaceutical accomplishments was his “insistence on thorough research and extensive testing before any product was put on the market.”

Mel James, author of the Library and Archives Canada article, wrote that the Frosst company was known for setting a North American industry standard in the percentage of research to sales. “He [Charles E. Frosst] was also a major supporter of hospital research and provided numerous scholarships to medical and healthcare students.”

As he grew the company, Frosst never strayed from his original commitment to expanding the R&D facilities. That included a line of veterinary drugs for small animals by the early 1940s, according to James’ article in Library and Archives Canada. By the 1940s, the company had also obtained a licence to produce Vitamin B2.

Library and Archives Canada specifies that Frosst insisted on selling only to licensed druggists, avoiding those who continued to rely on old-time remedies and hypnotic compounds. “This policy encouraged hospitals to deal directly with his company and they soon became his biggest customers.”

A visionary business leader

In the field of pharmaceutical research and production, Frosst was a visionary. He was known to have machinery built to his specifications to manufacture new product lines. He always managed to hatch innovative promotional ideas to attract press coverage for his medicines.

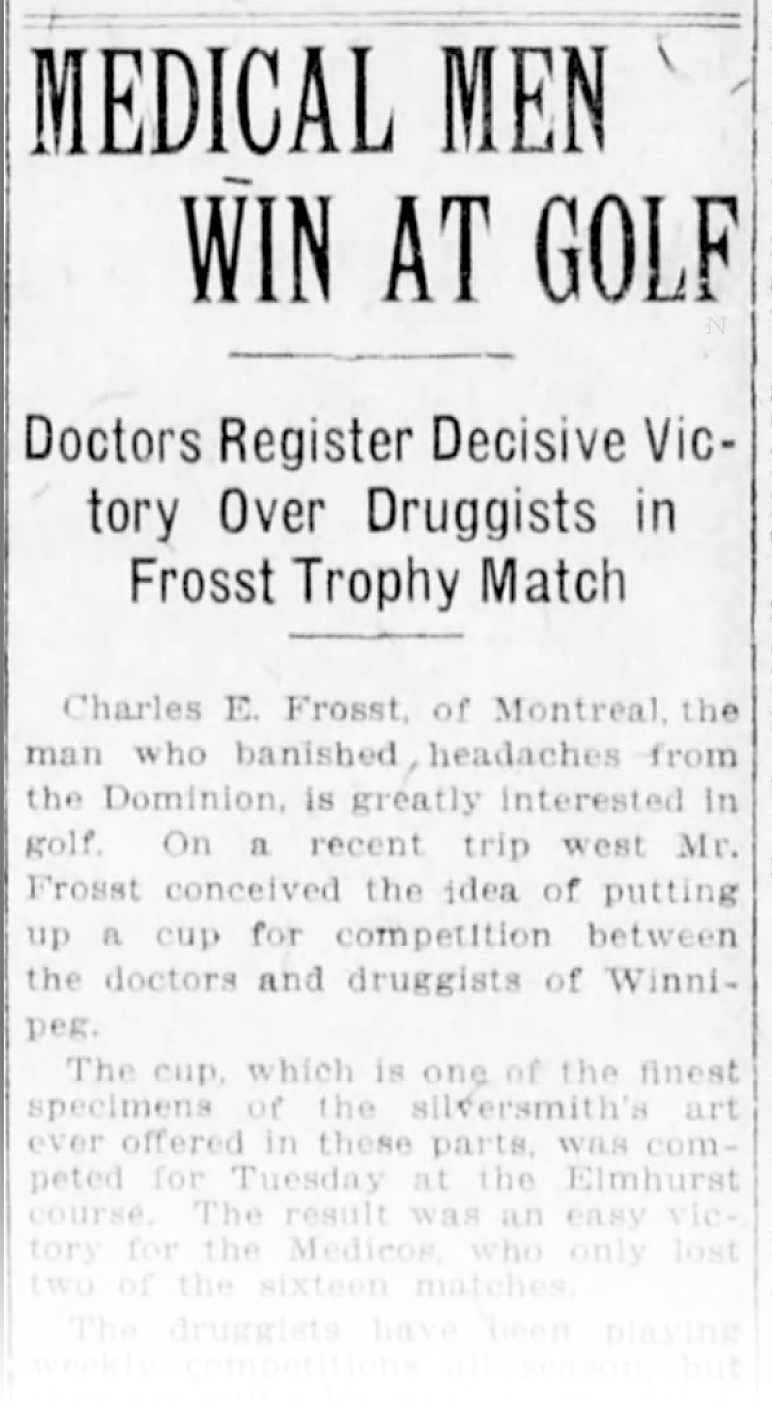

For example, in September 1921, Frosst organized the first annual golf tournament pitting two teams competing for the newly created Charles E. Frosst Trophy at the prestigious Elmhurst Golf & Country Club in Winnipeg. The contest had pharmacists competing against medical doctors. Frosst made sure the event came to the public’s attention through The Winnipeg Tribune. The newspaper glowingly called him “the man who banished headaches from the [British] Dominion.”

The newspaper described the trophy cup that Frosst commissioned for the winning golf team as “one of the finest specimens of the silversmith’s art ever offered in these parts.” The doctors easily won, The Winnipeg Tribune reported on September 21, 1921. The newspaper reported tongue-in-cheek that the doctors had prescribed Frosst’s Blaud capsules to combat iron deficiency in order to give more energy to the pharmacists for any future competition between the teams.

Within his company, Frosst was recognized as a progressive manager who treated his employees like family. He distributed annual bonuses based on the company’s financial year-end. He understood that his employees were the backbone of business success and his growing reputation as an innovator in the field of pharmaceutical R&D.

In their December 24, 1936 edition, the Montreal French-language daily newspaper La Patrie described the company’s annual, catered Christmas dinner. At that party. Charles E. Frosst’s son, Eliot, distributed bonuses as a thank-you to the staff. La Patrie wrote that the “very satisfying” relationship between management and staff was due to the founder’s “personal interest in the well-being of his employees”.

La Patrie reported that Frosst offered group insurance to his staff, as well as a pension plan paid for by the company, and excellent “hygienic” work conditions in “spacious” offices and “vast” laboratories. La Patrie summarized that “since it started, the company has steadily improved its manufacturing of high-quality pharmaceutical products and is recognized everywhere as one of the top of its kind [pharmaceutical manufacturers] in Canada.”

By the 1920s, the original 2,000 s.f. (186 square meters)) lab on Dufferin Square had moved into a 50,000 s.f. (4,645 square meters) building on St. Antoine Street W., the same downtown street that housed The Gazette, Montreal’s venerable morning daily newspaper founded in 1778.

Annual picnics – as reported by The Gazette and dating back to the summer of 1920 – were eagerly anticipated by staffers, as well as by Charles E. Frosst himself. There were entertaining sports events held at the picnics, such as intra-company baseball games, 100-yard dashes, three-legged hops, and sack races. Dance competitions with prizes for the most graceful waltzes were favourites. When possible, the day-long picnics were staged near lakes or rivers to afford participants access to swimming and boating.

The Gazette reported in December 1931 details of Frosst’s annual Christmas party held at the festively decorated company offices on St. Antoine Street W. The 120 Frosst employees sang Christmas carols with their bosses as they were wined and dined with a full-course meal prepared by the company chef.

On June 23, 1939, The Gazette reported that 300 doctors and their wives attending the Canadian Medical Association convention in Montreal were guests at a buffet dinner hosted by Frosst at his company offices. Frosst did not miss that opportunity to give his guests a tour of the company’s “new research and control laboratories”.

The online profile written by Mel James and posted by Library and Archives Canada states that “the senior Frosst had a management style that is today described as ‘management by walking around.’

“Although he presented a stern image, he made a point of knowing the names of all employees, how many children they had, what their interests were,” James wrote. “Employees were encouraged to take pride in their work and learned that they could always approach him [Frosst] if they had a problem. He was also known for his sense of humour as evidenced by his annual sponsorship of the ‘Dingbat’ calendars, waggish cartoons facetiously caricaturing the medical and pharmaceutical professions.”

A shared sense of humour

Undoubtedly, Charles E. Frosst’s sense of humour and appreciation of the impish nature of Dudley Ward’s Dingbat characters was the principal bond that united these two otherwise diametrically, opposed personalities. One was a successful, wealthy businessman who was a pillar of Montreal society; the other was a supremely talented but peripatetic artist often ensnared in civil litigation as he hustled gigs to augment spotty finances.

Ward, who specialized in surrealism and cartooning, loved his funny Dingbat characters. He used them in paintings throughout his life. In The Canadian Bookman published in April 1919, art expert St. George Burgoyne recognized Ward for his imagination and drawing skills.

After starting his art career at age 14, Ward studied at what is now the Royal College of Art in London. He also took lessons in Amsterdam and Brussels before moving to Canada in 1910. In his 1919 book, Burgoyne cites Ward as being in the category of a “striking and novel” illustrator “best known by his whimsical pictures of Dingbats – fantastic, gnome-like figures.”

Ward mixed his own colour pigments which bestowed his watercolour paintings with an ethereal vibrancy. He began his career as a cartoonist with the British comic strip magazine Ally Sloper and was published in other British humour magazines such as Sketch, Illustrated London News, and Bystander. In Canada, his artwork appeared in Maclean’s, Canada Weekly, Courier, Globe and Mail, and Everywoman’s World.

While he was known to the public as an exceptional artist, in his private life Ward was an avowed bohemian. He was a nonconformist who had he been born 70 years later – in 1949 rather than 1879 – would have undoubtedly grown up to be a hippie/flower child of the 1960s.

When Ward arrived in Montreal in 1910, Canada was a self-governing dominion of the British Empire, which controlled Canadian foreign policy. So four years later in 1914, when Great Britain declared war on Germany as part of the First World War, all parts of the British Empire, including Canada, went to war in support of the mother country.

Until January 1, 1947, all Canadians carried a British passport and were considered to be British subjects because there was no legal designation for Canadian citizenship. That meant that when they immigrated to Canada in 1910, Dudley Ward and his family were accorded the same legal rights and privileges as all Canadians, but they remained British subjects.

[Editor’s Note: The Canadian Citizenship Act that took effect on January 1, 1947 allowed people born in Canada – for the first time – to be legally designated as Canadian citizens. According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, the first person to register as a Canadian citizen was Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.]

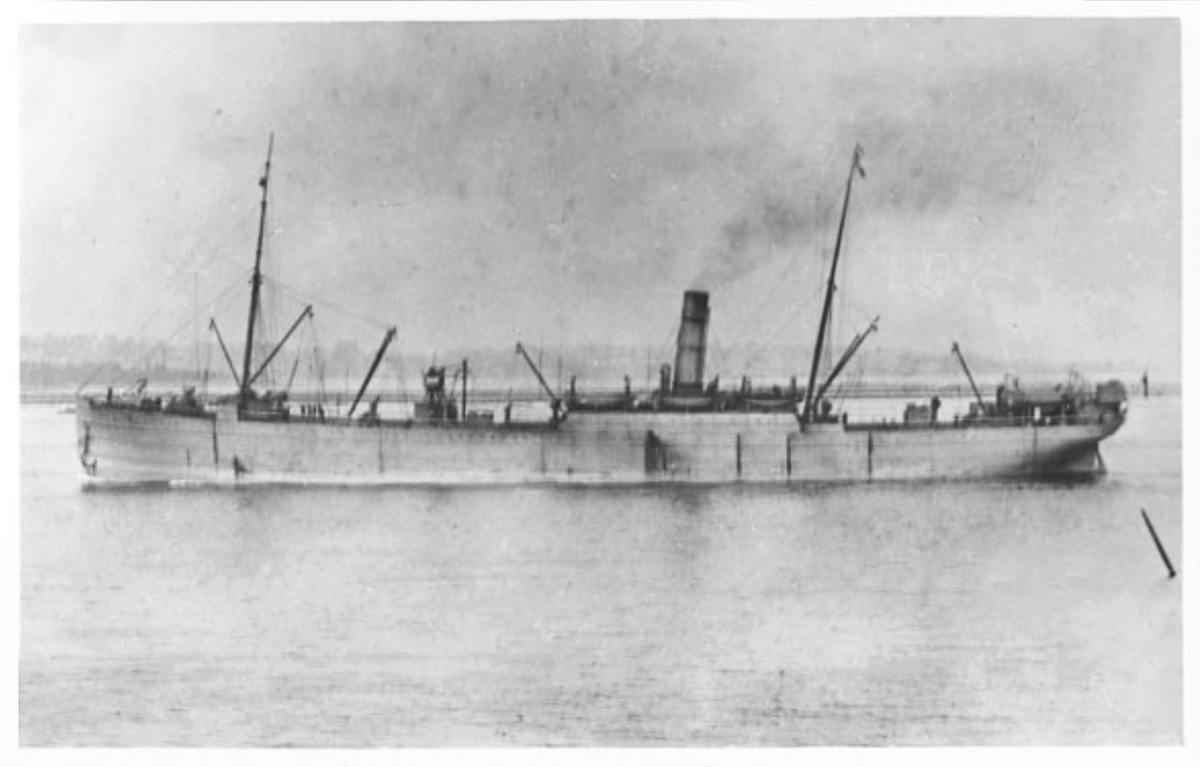

So given its close cultural and legal ties with Great Britain, Canada in 1910 was a haven for a young Brit such as Ward looking for a fresh start far from his legal problems and complicated relationships in England. On October 6, 1910, Ward arrived in Montreal from London aboard the ‘Pomeranian’ passenger ship with his second wife, Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith (maiden name), who was 10 days short of her 20th birthday.

Aboard the ship with Ward and his wife, Dorothy Nellie, was their baby daughter – also named Dorothy – who was two weeks short of her first birthday. With them was Ward’s almost 5-year-old son, Harold Percy, whose mother Ethel Mary Emerson (the maiden name of Ward’s first wife) had died at the age of 22 just days after giving birth to her son on December 8, 1905.

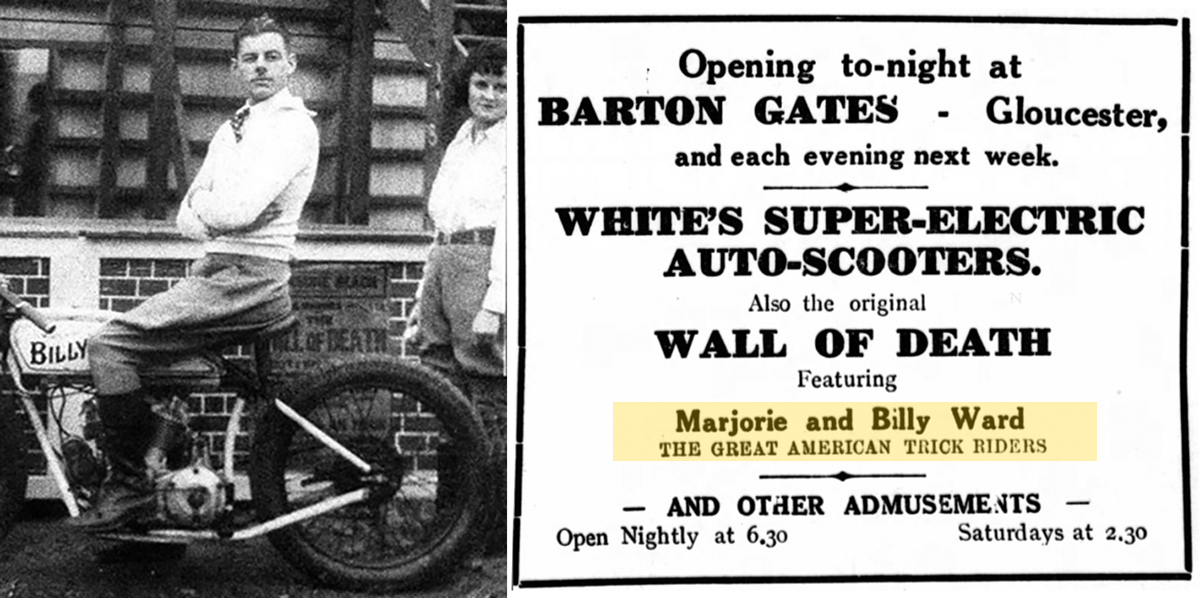

Saga of ‘Fearless Billy Ward’

Son Harold Percy turned out to be a chip off the old block in terms of his rebellious, devil-may-care attitude. He would go on to a headliner career as an intrepid motorcycle stunt rider performing in circuses around the world under the name ‘Fearless Billy Ward’. The Port Talbot Guardian of Wales reported on September 12, 1930 about the “thrilling stunts” performed by ‘Fearless Billy Ward’ and his Hong Kong-born wife, ‘Daredevil’ Marjorie Ward, also a motorcycle stunt rider.

Fearless Billy’s wife, Marjorie Ward, was a fitness fanatic who once confided tongue-in-cheek to Sir Malcolm Campbell – a world-class British race car driver and speedboat record-holder – that her major vices were cigarettes and chocolate. All thanks to Billy’s influence, she would say with a laugh.

Together, the swashbuckling couple defied the circus ‘Wall of Death’ driving horizontally on a straight wall between 70 m.p.h. and 100 m.p.h. (112 kph and 160 kph). “Must be seen to be believed,” a reporter for the Port Talbot Guardian wrote in 1930. The journalist went on to write that “the spectators gasp with amazement at the sheer brilliance of the driving when the riders – with arms outstretched – ride round at the same great speed.”

The racing glory that would accrue to Dudley Ward’s son, ‘Fearless Billy’, was far in the future on that Thursday, October 6, 1910 when the ship arrived in Montreal from London with Ward and his young family looking for a fresh start. Canada may have seemed like it could be a new beginning for Dudley Ward, but his headstrong, stubborn independence almost guaranteed that he would face the same existential challenges.

Consider the irony that for two decades Dudley Ward, an artist and a rabid anti-vaxxer, would go on to create annual Dingbat calendars to promote Charles E. Frosst’s pharmaceutical company that prided itself on innovative medicinal discoveries – including vaccines.

Back in England in 1906, just one month before the first birthday of his son, Harold Percy (a.k.a. ‘Fearless Billy’), Ward had been hauled before a judge to answer for breaking the law by refusing to have his infant son inoculated. Despite being fined 20 shillings and court costs by the magistrate and ordered to have his son vaccinated within 14 days, Ward continued to defy the judge, telling him that he would not obey his ruling. Those judicial proceedings were reported by The Harrow Observer of London, England on November 9, 1906.

Then there was the lawsuit of 1908 whereby Watford builder Harry Everitt had sued Ward for £17 in back rent and repairs to a house that the artist had rented from him. Whereas the builder had a solicitor represent him in court, Ward acted as his own counsel, telling the judge that he had “limited means”. The judge ruled against Ward, saying that he “could not see what possible defence defendant had.” He ordered that the plaintiff be paid the £17 within eight months, according to a report in the April 17, 1908 edition of The Harrow Observer. There was no follow-up article as to whether the judgment amount was ever paid.

On December 11, 1908, The Harrow Observer ran another story about Ward seeking bankruptcy protection from the court for unpaid bills related to the funeral of his first wife – Fearless Billy’s mother, Ethel Mary Emerson – who died in December 1905. Under the headline, ‘An Artist’s Difficulties’, the newspaper reported that the judge ordered Ward to pay his creditors the full sum owed, although the amount was not reported.

One might assume that Dudley Ward was too proud or not on good enough terms with the well-to-do parents of his first wife to ask them for help in paying for the funeral of their daughter, Ethel Mary. Ethel Mary was the sixth of 10 children born to Charles and Betsey Emerson in the English resort town of Scarborough on the North Sea coast.

Michael A. Barton, a retired fine arts faculty lecturer in the U.K., said in an email interview with BestStory.ca on August 8, 2024 that Charles Emerson owned two large stores – one that sold fish and game supplies and the other that sold glass and china wares – which he had inherited from the family of his wife, Betsey Cockerill (maiden name). They also rented out boarding rooms in the Saxony Hotel in Scarborough.

Michael A. Barton – whose great-grandmother, Florence Emerson, was one of Ethel Mary Emerson’s sisters – described the Emersons as “well off”. He told BestStory.ca that Dudley Ward’s parents – James William Townsend Ward and his wife, Clara – were farmers near the village of Cheadle in Staffordshire in the English Midlands about 170 miles (274 km) southwest of Scarborough.

An 1881 England Census indicates that the Ward farm at that time was 60 acres and that James William Townsend Ward employed “two men and one boy” to help him work the fields. Dudley Ward was born in Staffordshire in 1879. But Michael A. Barton told BestStory.ca that “at some point” after Dudley Ward’s father died in 1893 at age 47, a teenage Dudley Ward and his family left the farm and moved to Scarborough.

The 1901 England Census lists Dudley Ward’s mother, Clara, as working in the “Lodging House Keeping” trade in Scarborough. Michael A. Barton speculates that “it is probable” that Dudley Ward met his first wife-to-be, Ethel Mary Emerson, through his mother, Clara, who may have been working at the Saxony Hotel where Charles and Betsy Emerson rented out rooms.

What is beyond speculation is that Dudley Ward had an eye for young, beautiful women such as Ethel Mary Emerson who was 22 years old and pregnant when they married in April 1905 in the West Yorkshire city of Bradford. It’s also known that Ethel Mary Emerson enrolled for art lessons, according to a report in the Derbyshire Courier of August 26, 1905 that listed her as being registered for an outline freehand drawing course.

After she died in December 1905 – likely as a result of complications giving birth to Harold Percy on December 8, 1905 – Dudley Ward was left a widower with an infant son to care for. Less than three years later – in October 1908 – he married another young, attractive woman named Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith who was 18 at the time.

Two years later – in October 1910 – Ward sailed away with his second wife, Dorothy Nellie, from his messy personal, financial, and legal entanglements in England. With them were Ward’s two young children: 1-year-old Dorothy, whom he had with wife Dorothy Nellie, and 5-year-old Harold Percy from his first wife, Ethel Mary Emerson.

Based on what they said in 2024 interviews with BestStory.ca, the descendants of Dudley Ward and his second wife, Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith, know very little about Dudley Ward’s first wife, Ethel Mary Emerson.

Dudley Ward’s grandson – Dudley G. Ward – is a retired photoengraver living in Florida. He told BestStory.ca In a January 30, 2024 interview that he has a 1905 painting done by his grandfather portraying what he calls “a beautiful witch” with a black cat on her shoulder and a mischievous Dingbat tucked tight up against her. He thinks based on a conversation he had with his father, Jack – Dudley Ward’s son – that the beautiful witch was a portrait of Dudley Ward’s first wife done the same year she died.

For descendants of Dudley Ward, creating a narrative about his private life is like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle relying solely on snippets of recalled conversations with those who knew him and archives documenting both his foibles and his achievements. And, yes, of course, one cannot understand the artist without studying his masterpieces.

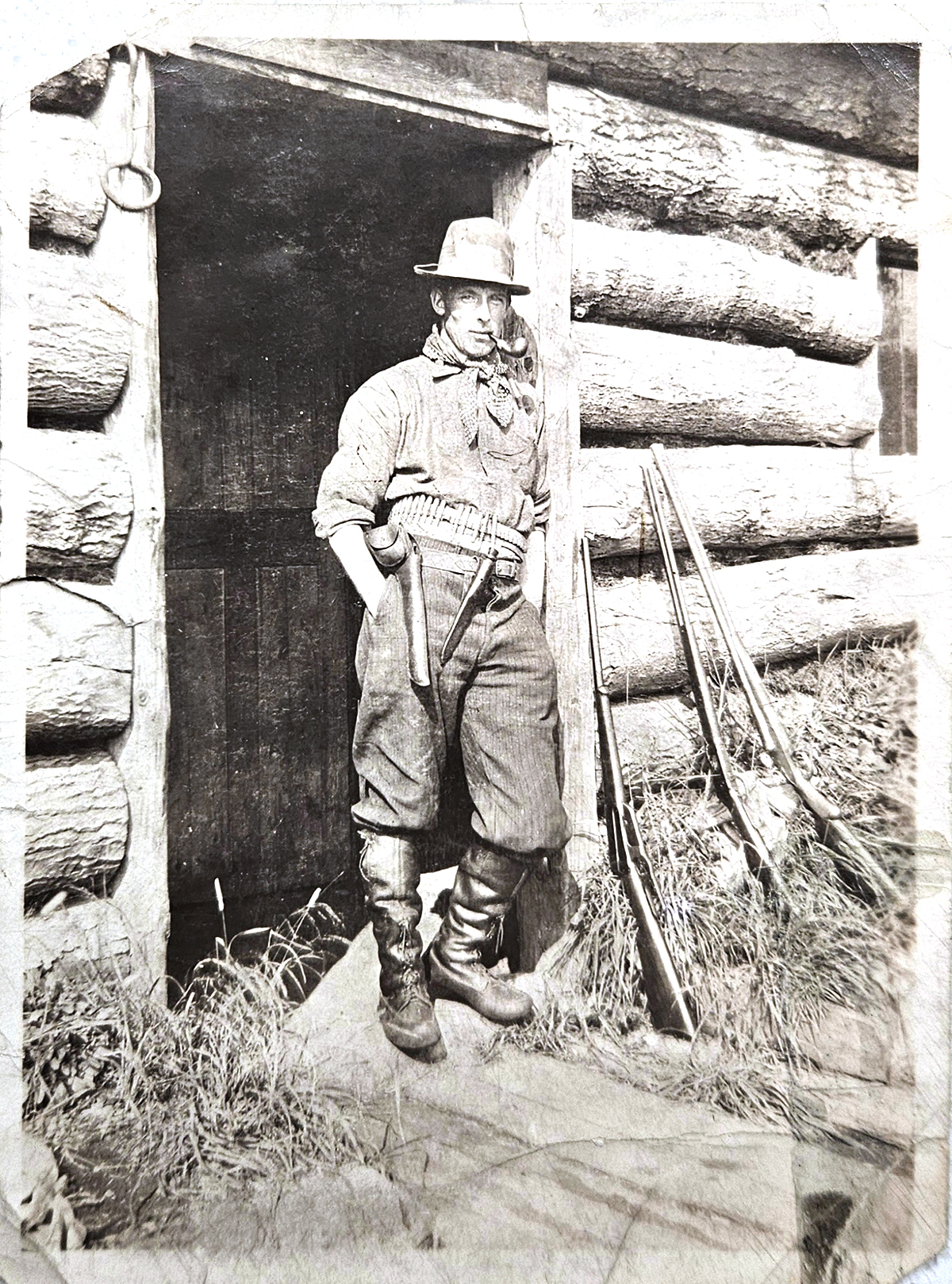

In a May 30, 2024 telephone interview from British Columbia with BestStory.ca, Dudley Ward’s granddaughter, Betty (Ward Wade) Edelmann, said that her mother, Dorothy (Ward) Wade, had told her that Betty’s grandfather, Dudley Ward, was an outdoorsman who enjoyed hunting and fishing and that “he loved people”.

“Yeah, he really enjoyed life. My mother always said that he was fun to be around,” Betty said about her grandfather. She added: “I guess he wasn’t too concerned about making money and paying bills.”

Although her grandfather was an anti-vaxxer, Betty said that her mother, Dorothy – who was born in 1909 and sailed to Canada from England with her family one year later – was vaccinated against polio when she was a young child. “So I don’t know whether that was my grandmother [Dorothy Nellie] putting her foot down or what… It could be that my grandmother kind of ruled the roost and said what was going to be done.”

Beautiful, bodacious fairies

As for her grandfather’s artistic abilities, Betty noted that he loved painting “truly beautiful” fairies, sometimes depicting them interacting with one of his beloved Dingbat characters. “The fairies that he painted, how very bodacious they were,” Betty said. “You know – curvy, busty, very sensual. Which probably says a lot about him.” One of her grandfather’s most famous paintings – ‘Fairy Sleep’ done in 1916 – is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada.

“I grew up with the Dingbat paintings and the Frosst calendars,” Betty told BestStory.ca. “I always knew that it was my grandfather who was the inventor of the Dingbat. I remember as a child looking at the Frosst calendars and kind of getting lost in them, making up stories.”

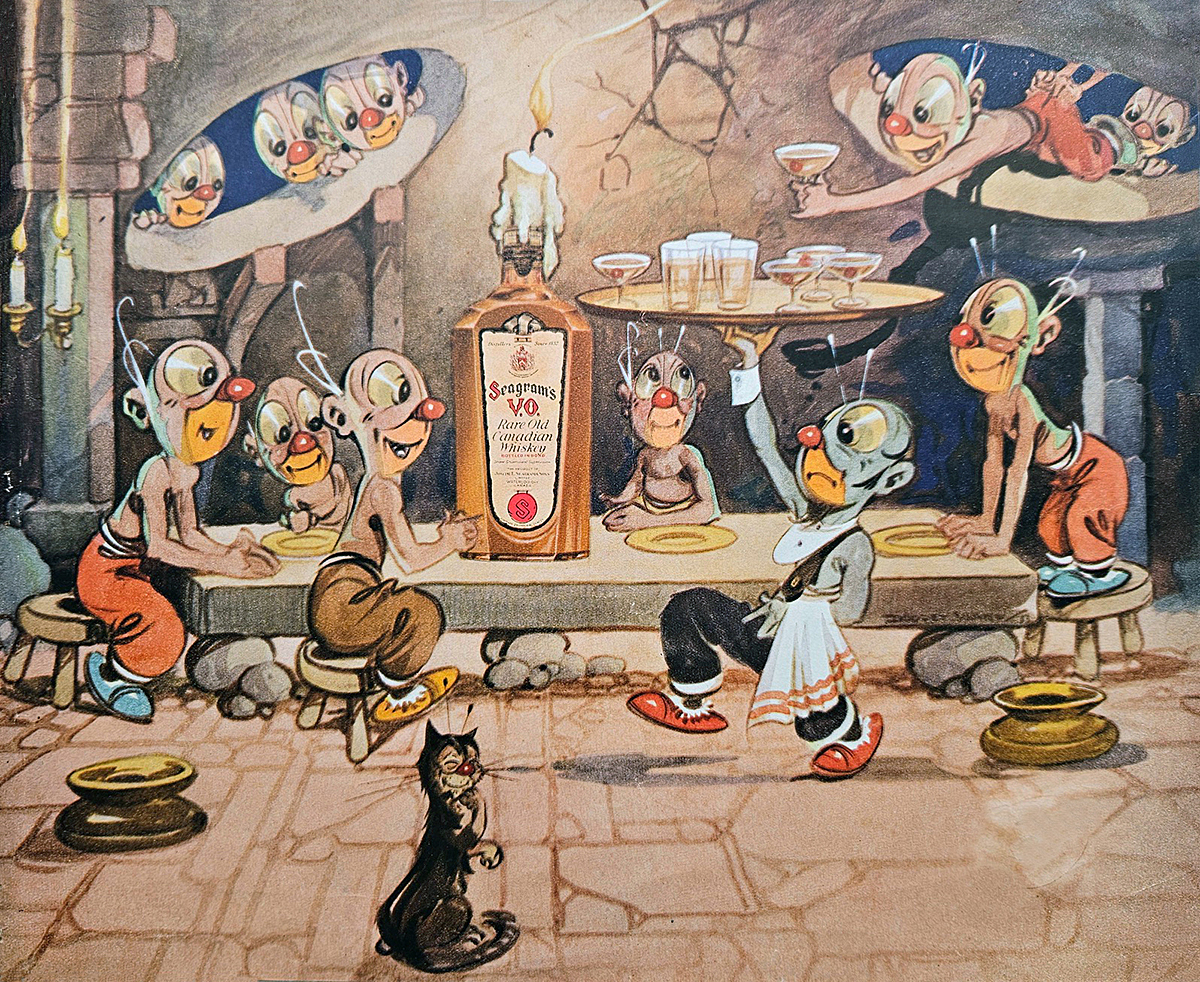

Frosst was not the only corporate client enthralled by the Dingbats. In 1921, Dudley Ward created a Dingbat ad and recipe book for Toronto-based E. W. Gillett Co. Ltd.’s Magic Baking Powder.* Ward also created a comical scene for a Seagram’s whiskey ad showing 10 Dingbats at a rectangular supper table watching with gleeful anticipation as a Dingbat waiter hurries towards them carrying a tray of cocktails and mixed drinks. During the same time frame of the 1920s to early 1930s, he created another Dingbat work of art for a Canada Paint hangtag.

*[Editor’s Note: American banker J. P. Morgan merged five American and Canadian companies in 1929 to form Standard Brands. Those five companies were Fleischmann; Royal Baking Powder; Widlar Food Products; Chase & Sanborn Coffee; and E. W. Gillett. By 1940, Standard Brands was the No. 2 after General Foods in packaged goods in the U.S.A., and by 1955 it was listed as No. 75 in the Fortune 500. After 1960, Standard Brands made several other acquisitions, including Planters, and in 1981 it merged with Nabisco to form Nabisco Brands Inc.]

Betty’s mother, Dorothy, was so proud of her dad Dudley Ward’s artistry that she collected a scrapbook with all the newspaper articles she could find about his artwork. She once told daughter Betty that Dudley Ward had been offered a job with Disney Brothers Studio in the 1920s, but that he preferred to stay in Canada.

Betty – the only child of Dorothy – never met her grandfather, Dudley Ward, who died seven years before she was born on March 21, 1942. But Betty does have memories of her grandmother, Dorothy Nellie, as being not too motherly and being very critical of her friends in the rock’n’roll era of Elvis Presley. “I never thought that she had much of a sense of humour,” Betty told BestStory.ca.

Betty said that her grandmother loved the romantic paintings of the Italian artist Pietro Aldi (1852-1888). “I have to say she was a little bit of a snob when it came to that,” Betty said in reference to her grandmother’s cultural tastes.

When Dudley Ward and his second wife, Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith, sailed into Montreal harbor on October 6, 1910, they came with two children: their 1-year-old daughter, Dorothy – whom Dudley Ward always called ‘Girlie’ – and Dudley Ward’s 5-year-old son Harold Percy from his first marriage to Ethel Mary Emerson.

One year later, on August 7, 1911, their son Jack was born in Toronto. Five years later, on August 4, 1915, Dorothy Nellie gave birth to another daughter whom they named Betty Constance: she died of diphtheria on May 13, 1928 at age 12. The descendants of son Jack Ward, who worked as a photoengraver, live in the United states, most of them in Connecticut and Florida. The descendants of daughter Dorothy (Ward) Wade live in British Columbia.

Upon arriving at the port of Montreal from England on October 6, 1910, Dudley Ward immediately relocated with his young family to Toronto. He did so because he knew it would be easier for a unilingual anglophone to find work in Toronto than in francophone Montreal.

Based in Toronto, he continued to create paintings with his Dingbat characters. They were viewed by the public at exhibitions in Ontario and Quebec, where Charles E. Frosst was first enraptured by one of the Dingbats in the summer or early fall of 1914. He immediately hired Dudley Ward – then living in Toronto – to produce the first Dingbat calendar for the year 1915.

In 1923, Ward and his family returned to Montreal after he was offered a job as a typesetter with The Gazette. His daughter, Dorothy, then 16 years old and a part-time artist’s model, joined him as a Gazette typesetter in 1925, according to an interview Dorothy gave to Bahai researcher W. C. van den Hoonaard. The interview took place in White Rock, British Columbia on July 15, 1990 when Dorothy was 80 years old.

When Dudley Ward moved his family from Toronto to Montreal in 1923, they first lived in the suburb of Outremont. Dorothy’s daughter Betty told BestStory.ca in the May 30, 2024 interview that her mother, Dorothy, told her that on Sunday afternoons during the 1920s the family would go for outings in their Model T Ford. But family matriarch Dorothy Nellie never trusted the car to cross any bridge. She also did not trust – or use – escalators in department stores.

[Editor’s Note: On October 13, 1962, Dudley Ward’s second wife, Dorothy Nellie, died from cancer and was buried in Prince George, B.C. A transcript of the interview that her daughter Dorothy gave to W. C. van den Hoonaard in 1990 was made available to BestStory.ca courtesy of University of New Brunswick Archives. In the interview, Dorothy says that she married Frederick G. Wade in 1937 and two years later they moved to Halifax where her husband worked in the dockyard. In 1948, she, her husband, and their 6-year-old daughter, Betty, moved to West Vancouver.]

Persistent money woes

But even after making a new home in Canada in 1910, legal and financial woes continued to plague Dudley Ward. It was a pattern that would persist throughout his life. On March 26, 1925, The Gazette reported that a judge had ruled in favour of Montreal-based Miller Lithographing Co. Ltd. vs. Dudley Ward for security to be deposited by the artist against judgment costs. The amount of the judgment was not reported.

The Gazette of June 6, 1932 reported on a court judgment of $192 with interest and costs in favour of Aloeric Pariseau vs. Dudley Ward. On May 22, 1933, The Gazette reported on another judgment, this one for $195 with interest and costs, in favour of Harry Fineman vs. Dudley Ward.

Is it any wonder that Ward’s daughter, Dorothy, reminisced in her 1990 interview with van den Hoonaard that her mother’s family “was horrified” when in October 1908 at age 18 her mother [Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith] married Ward, a widower with an almost 3-year-old baby (Harold Percy).

“They didn’t approve of it [the marriage] at all,” Dorothy said. “She [mother Dorothy Nellie Goldsmith] had been going up to London to take voice lessons, had a lovely voice,” Dorothy told van den Hoonaard. “She got her first appointment and then all this happened. Much to her horror, she was marrying, and marrying an artist.”

Perhaps due to his independent nature or the myriad court judgments hanging over his head, Ward was an elusive man to track down – even for art connoisseurs seeking to fete his brilliance. While living in Toronto in 1921, Ward was the subject of a search by Eric Brown, director of the soon-to-open National Gallery of Canada. All Brown wanted was biographical information on Ward to go with art work that was to be exhibited.

But Ward was nowhere to be found. In frustration, Brown wrote a letter dated February 15, 1921 to his colleague, E. R. Greig, curator of The Art Gallery of Toronto. “Have you any information about Dudley Ward in your possession?” Brown asked. “He has not replied to my inquiries and I have no knowledge of his whereabouts. If you can possibly fill in any of the enclosed form, I should be very grateful.”

On February 22, 1921, E. R. Greig replied to Eric Brown: “He [Ward] is still in town I believe, but I have not seen him for nearly a year…am making some inquiries…”

Dudley Ward’s erratic, nonconformist behaviour could be forgiven by colleagues, friends, and even astute businessmen such as Charles E. Frosst because it was overshadowed by an aura of creativity and mystique emanating from his artistry. He was a savant of wizardry who could create an endless stream of whimsical, imaginative scenes featuring fairies and his beloved Dingbats – both in his own paintings and in Frosst’s annual calendars.

But the Dingbat calendars faced an existential crisis when on Sunday, February 24, 1935 – one year after being diagnosed with stomach cancer – Ward died at age 55 in his home on Ile de la Visitation Street in the working-class area of Ahuntsic/Cartierville in northeast Montreal.

News of his death was carried by newspapers across Canada and beyond. The Toronto Telegram and Ottawa Citizen of February 25, 1935 carried a Canadian Press report that called him “a leading Canadian artist”. He was remembered for his exquisite artistry in the March 1, 1935 edition of his hometown Derbyshire newspaper, citing his 1916 watercolour ‘Fairy Sleep’.

For Charles E. Frosst, Ward’s death was the loss of a collaborator whom he respected and relied upon to produce original Dingbat artwork. He now faced the challenge of finding an accomplished artist who could copy the style of Ward’s Dingbats and continue to paint scientific/medical scenes for Frosst’s annual calendars.

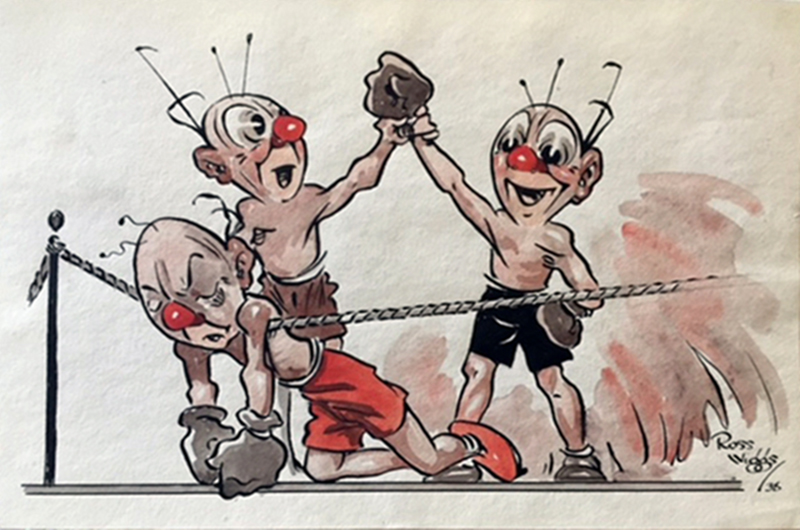

In the one year between his cancer diagnosis and his death in February 1935, Ward created three years worth of Dingbat illustrations for the Frosst calendars: 1936, 1937, and 1938. For the 1936 calendar illustration printed one year after his death, Ward drew what appeared to be a self-portrait reference showing a sick Dingbat lying in bed with concerned Dingbats hovering around him. The title of the illustration was ‘An Emergency in Dingbat Land’.

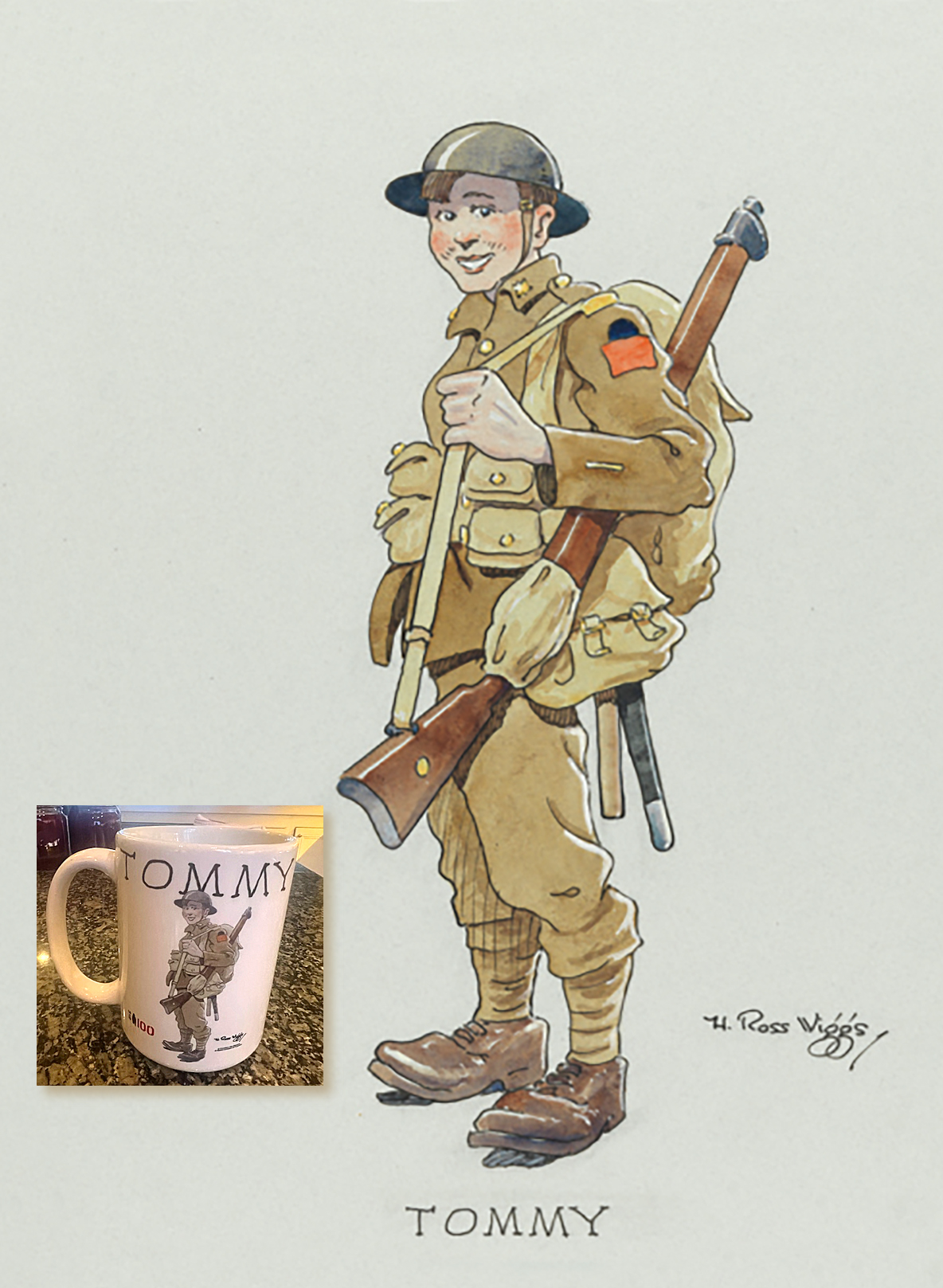

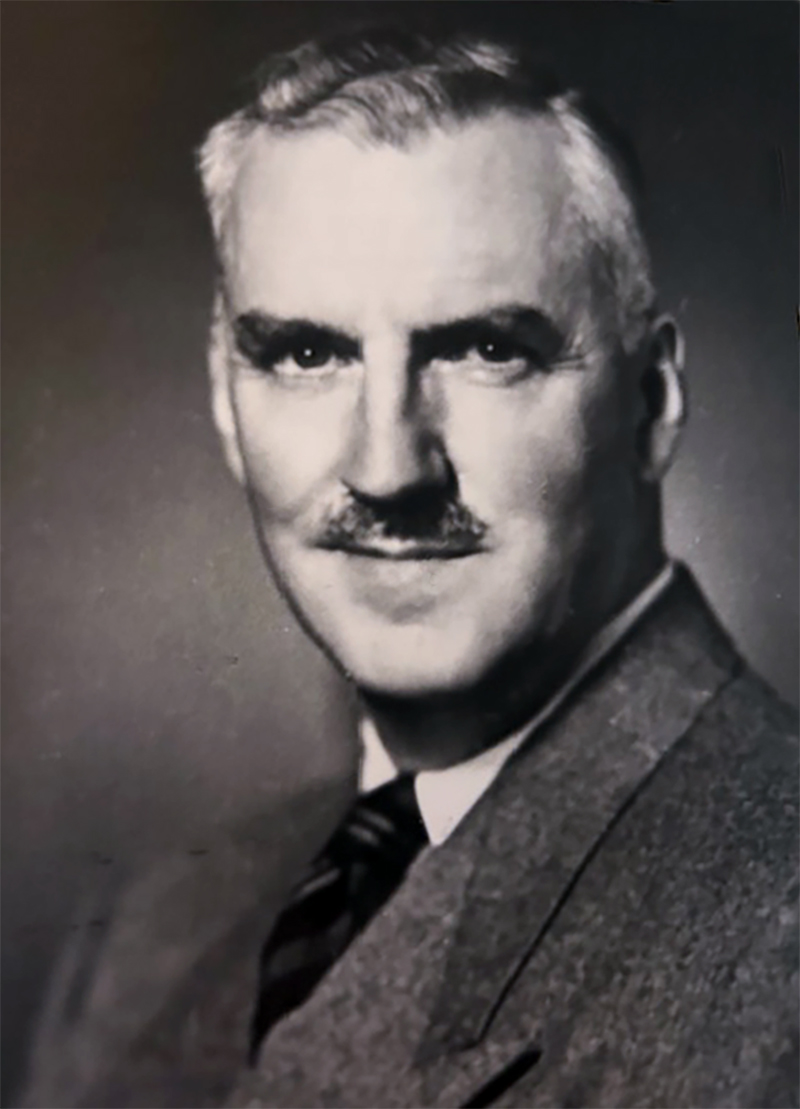

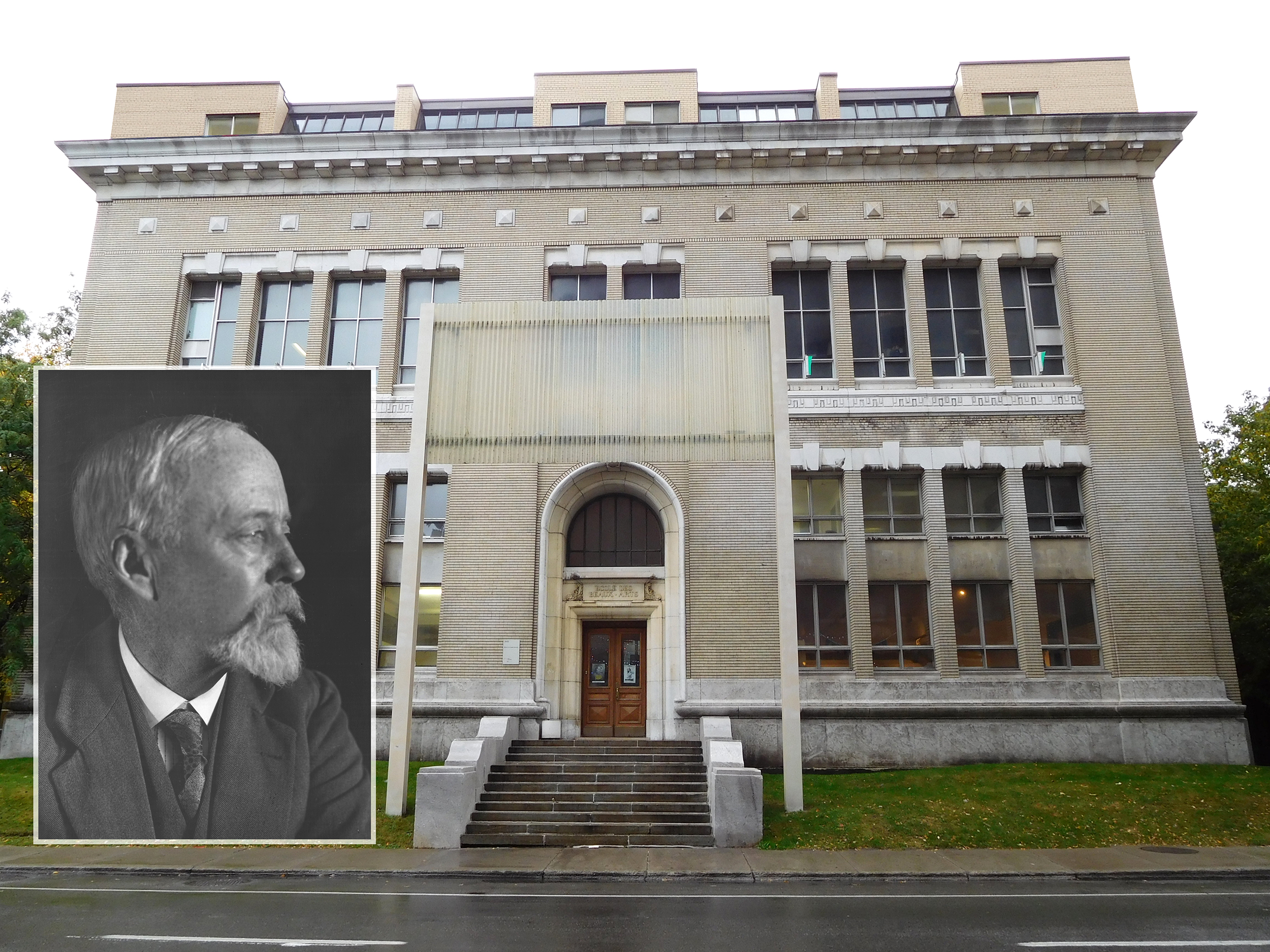

Thanks to Dudley Ward’s foresight in producing three posthumous calendar illustrations, Charles E. Frosst had adequate time to find a new Dingbat illustrator. And he didn’t have far to search: Lorne Wiggs, a prominent consulting engineer who was then doing work for the Frosst pharmaceutical company, immediately recommended his brother, Ross Wiggs (1895-1986), himself an award-winning Canadian architect and an accomplished artist who had started painting at age 10.

Ross Wiggs was a graduate of McGill University and MIT in Boston, where he obtained an architectural diploma in 1922. He worked for the next five years in New York City before returning to Montreal where he eventually founded his own firm in the middle of The Great Depression in 1933.

Wiggs was the architect for numerous commercial and industrial buildings in the Montreal area, as well as for homes in the tony suburbs of Town of Mount Royal and Westmount. He designed multiple country residences in St. Agathe, 60 miles (100 km) north of Montreal.

In 1940 he made the drawings for the world-famous Mont Tremblant ski lodge, country inn and cottages for Philadelphia-born developer Joseph Bondurant Ryan. The ‘Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada’ describes Wiggs as “a brilliant delineator” who “was much in demand…for his exquisite atmospheric pencil drawings that were often influential in capturing awards and prizes…”

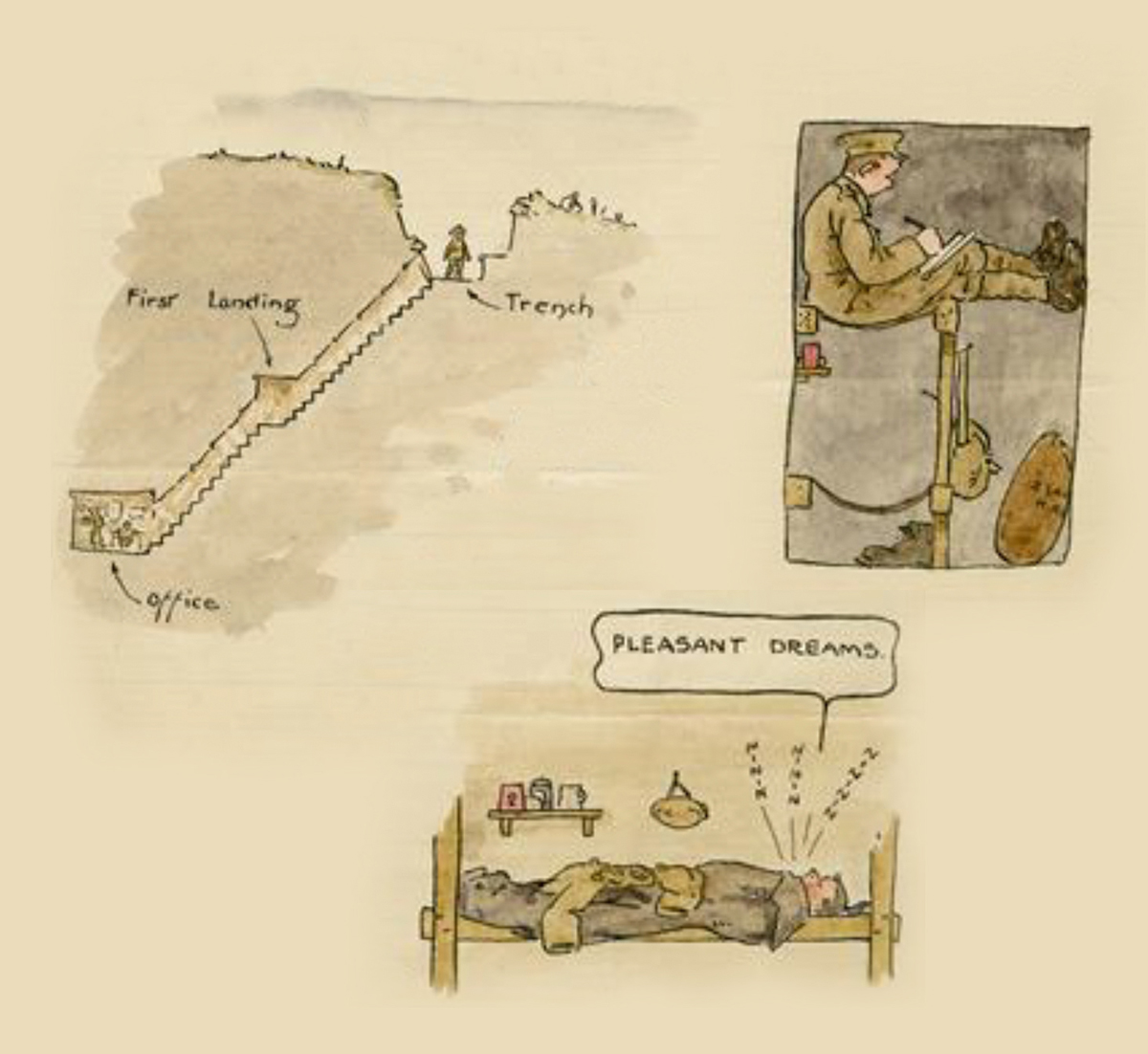

Art was mainly a hobby for Ross Wiggs the architect even though he has numerous paintings to his credit with some on exhibit in the Canadian War Museum. Among the paintings are scenes from the First World War in which Wiggs served overseas after graduating from McGill University and enlisting on April 25, 1917 with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He arrived in England on July 5, 1917.

Dingbat artist No. 2

It seems that his artistic ability kept Ross Wiggs safe from enemy bullets after his military unit travelled to the front lines in France on April 30, 1918. Letters he wrote from the front line also shine light on a crush he had on a young woman named Alice Common.

In a letter dated May 15, 1918, he wrote to his “friend” Alice that he was ensconced “in a tunnel 50 feet underground” where he was “in charge” of drawing all the “fighting maps” and sketches for his military unit. That letter and another one he wrote to her on November 7, 1918 can be found in the Canadian War Museum, which also has a b&w studio portrait of her in its George Metcalf Archival Collection.

Reflecting his artistic nature, the 22-year-old Wiggs illustrated his three-page letter of May 15, 1918 with 12 small, coloured drawings depicting both civilian and military scenes. He made a point of reassuring Alice that although his underground “home” was cramped, it was safe. With a bunk bed further along the tunnel, he described his abode as “quite comfortable down here and quite out of reach of any fritz [German] shells and fast-flying fragments.”

The letter to Alice took the better part of an evening for Wiggs to compose as he wedged himself into tight quarters with knees bent and feet pressed against the earthen wall across from him while he kept his eyes peeled for foraging rats. He ends the letter by writing: “As it is near midnight, it is time I should go to bed. I generally turn in at nine, but it has taken me all evening to write this letter. Now don’t you think I’m pretty good to take up a whole evening to write to you? I wouldn’t do it for anyone else.”

It is obvious that Ross Wiggs had romantic feelings towards Alice Common. In his letter, he refers to the possibility of her getting married in the near future. “Everybody seems to be getting engaged these days,” he wrote. “So I suppose the next thing we’ll hear will be that Miss M.A.G.C. has made the ‘fatal plunge’. Who is going to be the ‘lucky dog’?” He ends the letter as follows: “Please write soon and as often as you can because, you know, I – well, you know – and that settles it, doesn’t it?”

According to ancestry.com, the initials M.A.G.C. cited in Wiggs’ letter of May 15, 1918 stand for Margaret Alice Gertrude Common whom it lists as having been born in Montreal in February 1895, making her 10 months older than Ross Wiggs who was born in Quebec City in December 1895. Ross Wiggs’ letter of May 15, 1918 indicates that his entire family – including his father William Henry Wiggs and his mother Emma Clara Wiggs – had warm feelings towards Alice Common, embracing her into their family circle.

Ross Wiggs and Alice Common were not the only romantic links between the two families. His sister, Edith, married Alice’s brother, dentist John S. Common, on June 8, 1922.

Ross Wiggs writes in his letter of May 15, 1918 that he was “glad to hear” that Alice had visited his family in Quebec City and “that they looked after you properly.” He goes on to write:

Father says that he has asked you to go down to New York and Atlantic City with them, so I hope you will go. It is a great trip and I’m sure they would see that you had a good time. I have already pictured the party down in Atlantic City on the big board walk. I suppose Father and Mother toured up and down in the usual fashion in one of those chair carriages… Mother always spends most of her time shopping.

There is no indication as to why what seemed to be a budding romance between Ross Wiggs and Alice Common did not lead to marriage. What is known through archives from ancestry.com and newspapers.com is that Alice Common went to Buffalo to enrol in a shorthand course in late August 1922 – 2 ½ months after attending her brother’s wedding in Montreal to the sister of Ross Wiggs.

Border crossing records indicate that she returned to Canada only on December 26, 1923 – meaning that she did not attend the July 28, 1923 wedding of Ross Wiggs, then 27, to Mildred Jean Watson, 26. Mildred was the daughter of a prominent family – Maj-Gen. Sir David Watson and Lady Watson. Her father was a successful businessman who had controlling interest in The Quebec Chronicle and was an influential member of The Canadian Press news-gathering cooperative.

When Sir David Watson died of a stroke on February 18, 1922, his funeral was attended by dignitaries from across Canada including Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and Quebec Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau. King George V of England sent the family a message of condolence.

As for Alice Common, ancestry.com and a census record indicate that she was still single in 1931 and living in Montreal with her youngest brother, Ernest. But four years later – on September 7, 1935 – The Gazette carried an announcement that in the following month Alice Common was to marry Massachusetts-born, widower Harold Charles Pearson, who had immigrated to Canada with his first wife, Evelyn, in 1930.

The marriage ceremony was held in the United Church in Westmount on Wednesday, October 2, 1935. The registry listed the 40-year-old bride as a “spinster”. Her husband, 38, was listed as a chemical sales manager who lived in the Town of Hampstead, a verdant municipality in the west end of Montreal. Alice Common became stepmother to Nancy and J. Bruce Pearson, but never had biological children.

Ross Wiggs and his wife, Mildred, had one child named Marjorie Wiggs. According to newspaper clippings, she was a debutante who enjoyed a weeks-long vacation with her parents in 1949, travelling to England and the Continent. Marjorie Wiggs, born in 1927, is the mother of Cynthia Grant, who supplied much of the biographical information and photos to BestStory.ca about her grandfather, Ross Wiggs.

The marriage of Alice Common took place eight months after the original Dingbat creator Dudley Ward died in February 1935 – an event that would lead to the ascent of Ross Wiggs as the second Dingbat artist a few years later.

Like Dudley Ward before him and the three other Dingbat calendar artists who followed him, Ross Wiggs was a man who did not trumpet his private life. He preferred to allow snippets of his nature to be gleaned through his art.

Prior to taking on the Dingbat mandate, Wiggs had studied art under Maurice Cullen (1866-1934) – one of the first impressionist artists in Canada – and William Brymner (1855-1925), a landscape painter who taught art classes in Montreal specializing in modernistic aspects of impressionism.

But even for a man of Wiggs’ artistic pedigree, following in the footsteps of Dudley Ward presented a major challenge in terms of Frosst’s directive that Wiggs should emulate as closely as possible Ward’s Dingbat cartooning style.

Lorne Wiggs had no doubt that his brother could succeed, telling Frosst that Ross “likes drawing caricatures” – which ignored the fact that most of Ross Wiggs’ artistic creations involved watercolour nature scenes and portraits done in chalk drawings; not caricatures such as the Dingbat scenes required.

In a series of email exchanges in January 2024, Ross Wiggs’ granddaughter Cynthia Grant told BestStory.ca that she has several of her grandfather’s original watercolors that he painted for the Dingbat calendar covers. Grant, who lives in Boston, made available to BestStory.ca excerpts from a self-published biography that her grandfather bequeathed to the family. In the diary, he describes the challenge of following in Dudley Ward’s footsteps.

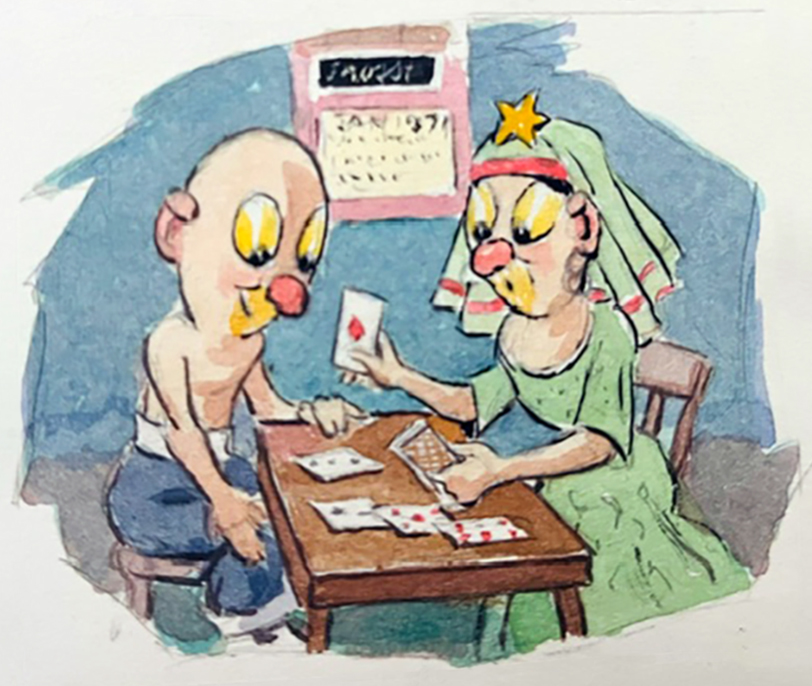

“So they [Charles E. Frosst & Co.] were looking for someone who could take his [Ward’s] place,” Ross Wiggs wrote. “The illustrations showed some small elves with large eyes, bald head[s], and pointed ears, engaged in medical projects pertaining to the products produced by the company in the form of caricatures and all in colour.

“I said I would be glad to try and see if I could imitate his [Ward’s] style. After submitting several sketches showing the Dingbats at work, I was authorized to go ahead with an illustration for the next calendar.”

Wiggs’ first illustration appeared in the 1939 Dingbat calendar. The Frosst company issued a statement saying that “we are fortunate in being able through H. Ross Wiggs to perpetuate the memory of Dudley Ward and to keep alive his Dingbats.”

The Frosst company statement went on to say: “Mr. Wiggs possesses originality of thought and a keen sense of humour. His smooth-flowing technique, almost identical to that developed by Dudley Ward, expresses a deep knowledge of composition and colour.”

Wiggs’ first illustration titled ‘A Ticklish Situation in Dingbat Land’ was described in the Frosst company statement as “one of the best studies of humour we have ever had the pleasure of presenting.” Under his signature, Wiggs wrote ‘as suggested by Dudley Ward’. It was an apparent homage to his deceased predecessor who seems to have come up with the idea for that particular Dingbat scenario. The scene showed a Dingbat patient in a hospital bed having his foot tickled by a nurse with other Dingbats looking on in glee and wonder.

For the next nine years, Wiggs continued creating the annual Dingbat calendars – which he described as “a lot of fun”. He wrote in his self-published biography that he got a kick out of seeing his version of the Dingbat calendars hanging on the walls of medical offices and pharmacies.

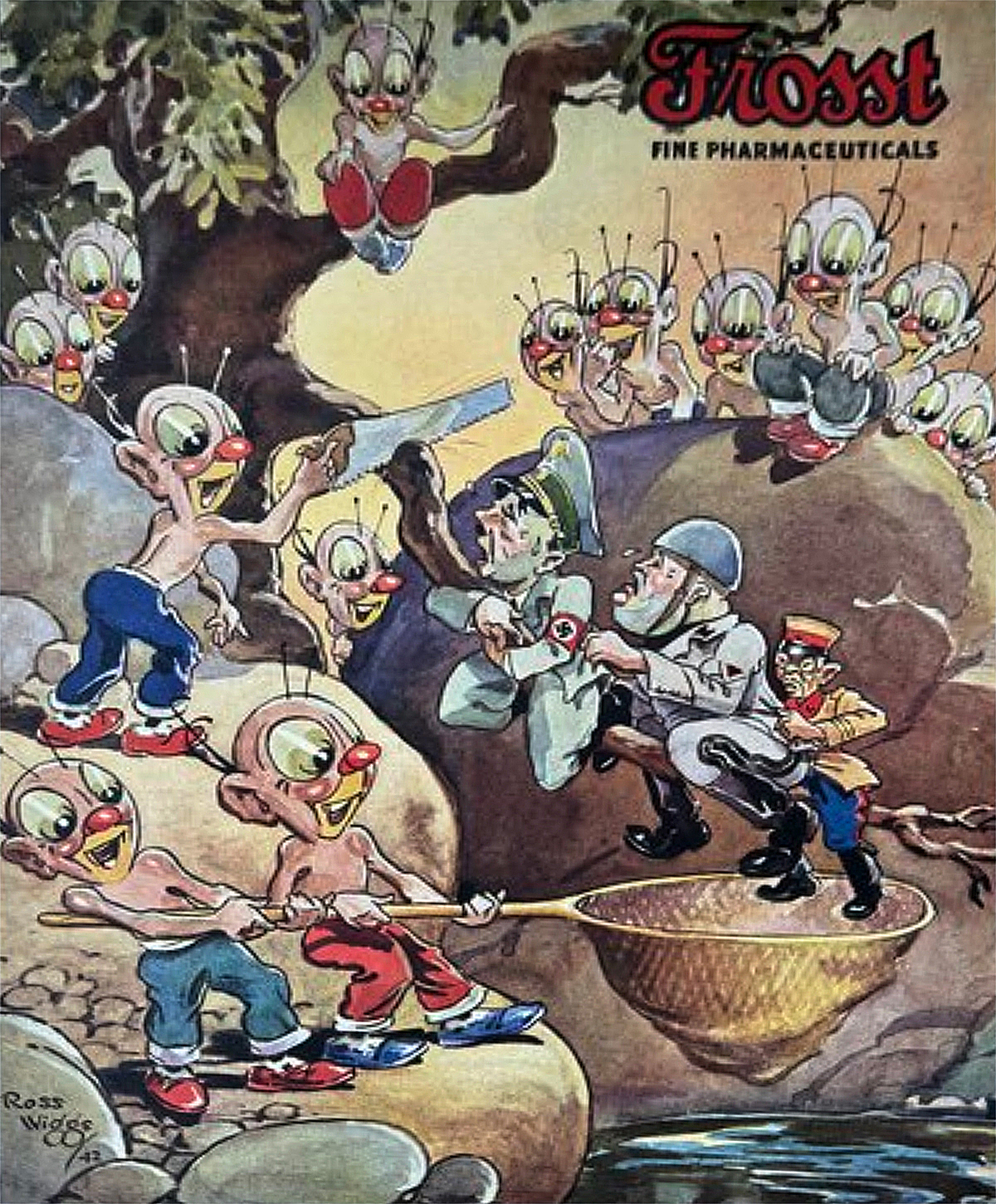

The 1942 calendar featured the boldest, most talked-about Dingbat illustration ever painted by the WW I veteran. It shows a group of Dingbats perched on a tree and a nearby boulder watching as one of their buddies saws a tree branch to which Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Hideki Tojo are clinging. On a lower rock, we see two Dingbats holding a big net ready to capture the three leaders of the Axis powers when they fall.

But as Wiggs became increasingly squeezed for time due to his very successful career as an architect, he found it difficult to carve out the necessary hours to create a new Dingbat calendar every year. The 1947 Dingbat calendar was destined to be Wiggs’ last.

Dingbat artist No. 3

For the 1948 Dingbat edition, Charles E. Frosst again reached out to a military veteran: Lawrence Robb Batchelor, a captain in the Canadian Army who fought in the April 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge, one of the bloodiest and most significant victories in Canadian military history.

[Editor’s Note: Some 3,598 Canadian soldiers died and 7,000 were wounded as Canadian troops overran German trench lines under withering machinegun fire during the three-day battle in Pas-de-Calais, France – adjacent to the Strait of Dover.]

Unlike Dudley Ward, the first Dingbat illustrator, Batchelor was not an anti-vaxxer. His medical certificate dated February 5, 1915 – when he enrolled in the Canadian Army – cites a “large vaccination scar on his left arm”.

Batchelor also fought overseas in the Second World War with the 17th Hussars and the Royal Montreal Regiment. Despite his status as a patriot who volunteered to fight in two world wars, Batchelor is probably best remembered as the third Dingbat illustrator chosen by Charles E. Frosst to create artwork for the annual Dingbat calendars.

Frosst didn’t have to look too far to find Batchelor who was a well-known artist born in Montreal on July 11, 1887. He started his career as a cartoonist with The Montreal Daily Star before he volunteered to enlist in the Canadian military during WW I.

[Editor’s Note: Frosst had great respect for the Canadian military, establishing the Charles E. Frosst War Services Group which raised money for medical treatment of war veterans and sent monthly food shipments to Canadian soldiers fighting overseas during the Second World War.]

Batchelor, who lived in the municipality of Pointe Claire on the West Island of Montreal, was a well-known wildlife illustrator. He also had drawings published in Canadian history books. One of his oil paintings depicting 17th century life in New France is preserved in a collection of Library and Archives Canada. As well, the cover illustration for the Government of Canada’s Vimy Memorial Guide Book was drawn by Batchelor to commemorate an historic ceremony presided over by King Edward VIII on July 26, 1936.

Judging by an antiques Q&A column published in the Waterloo Region Record of September 17, 2016, Batchelor had his own following among Dingbat aficionados during his 14-year Dingbat reign. John, a reader from Point Edward, Ontario wrote to the newspaper’s antiques columnist asking whether he had made a good deal in paying $50 at a flea market for a damaged 1954 Frosst Dingbat calendar. It was illustrated and signed by R. Batchelor. Newspaper reader John described Batchelor’s Dingbat illustration as “colourful and loaded with lots of cartoon action,” adding “I loved the graphics.”

The answer that John received in the newspaper from the unnamed columnist surely lifted his spirits. “There is always interest in good graphics, and I’d say this piece is well worth the price you paid,” the columnist wrote, adding that Dingbat calendars “are tough to find.”

In fact, Dingbat calendars are still considered valuable collectibles with some used editions from the 1990s listing in 2024 for between $43 and $260 Cdn (between $31 and $190 U.S.) at online sites such as Etsy and eBay. A UK website called ‘The Book Palace and Illustration Art Gallery’ still sells poster reprints of Dingbat calendar illustrations created by Batchelor, Wiggs, and Ward.

The Waterloo Region Record antiques columnist went on to write in his column of September 17, 2016 that Charles E. Frosst was the first manufacturer in Canada to develop radioactive pharmaceutical products, alluding to Batchelor’s 1954 Dingbat scene entitled, ‘The Dingbats Take to Atomic Energy’. Such radioisotopes are used to this day to diagnose and treat diseases such as cancer in specific organs and cells in the human body.

Batchleor stayed at his Dingbat post for Frosst until his death at Queen Mary Veterans Hospital on May 14, 1961 at age 73 following a lengthy illness. He was survived by his wife, Rosa Celine Saison Batchelor, whom he had met at Pas-de-Calais where the Battle of Vimy Ridge took place. With permission of the Canadian Army, the couple wed in France on April 27, 1918. Their wedding took place less than six months before WW I officially ended with the signing of the Armistice of Compiègne on November 1, 1918.

[Editor’s Note: Rosa Celine passed away on November 29, 1994 in Montreal. The Batchelors’ two children – Bernice and Lorne – were both born in Canada, but are deceased.]

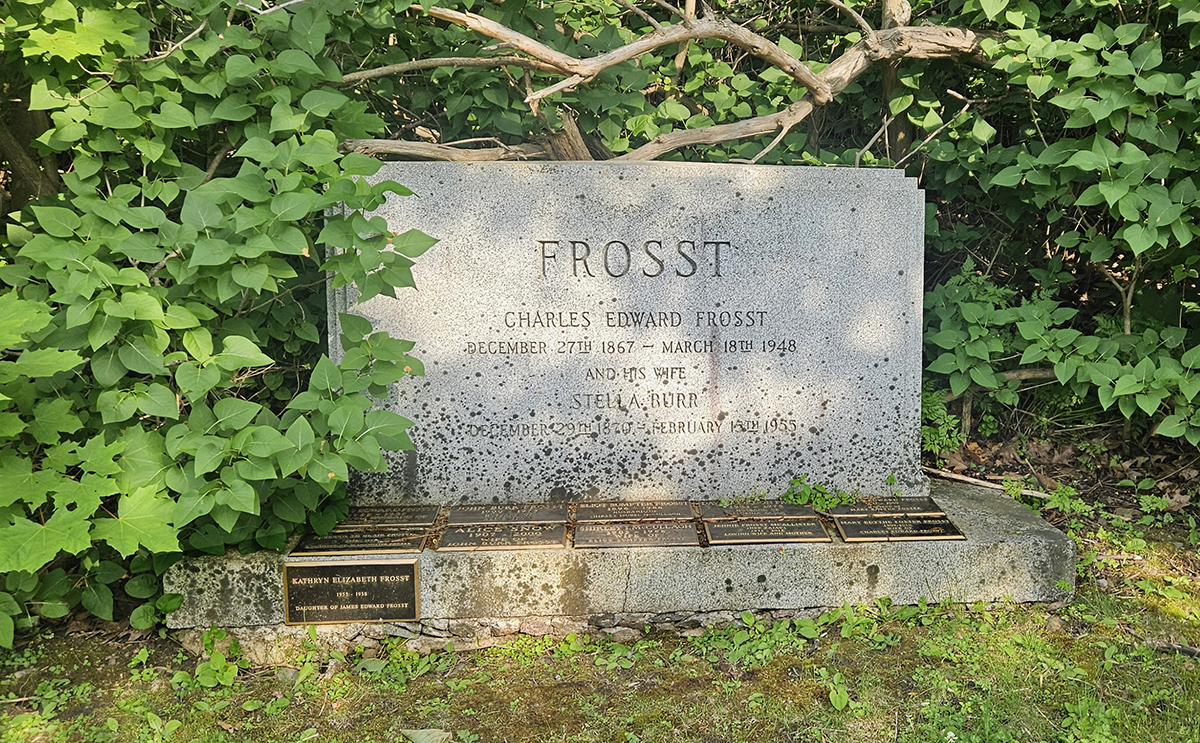

Such was the growing popularity and fame of the Dingbat calendars that over a period of 78 years they survived the passing of the individual artists who created them, as well as the sudden death on Thursday, March 18, 1948 of Charles E. Frosst, the visionary entrepreneur who first commissioned the 1915 Dingbat calendar from artist Dudley Ward.

Passing of a giant

The death of Frosst, 81, at his Westmount home at 17 Forden Avenue shocked the social elite of Montreal. Eulogies poured in. The Gazette of March 19, 1948 described him as “one of Canada’s pioneer industrialists” as “chairman of the board of the internationally known pharmaceutical firm which bears his name.”

The Gazette noted that although both Charles E. Frosst and his wife, Stella, were married in their home town of Richmond, Virginia in 1895, they returned to raise a family in Montreal where Frosst had been working as a salesman for Wampole since 1890 before founding his pharmaceutical enterprise in 1899.

The Gazette eulogy of March 19, 1948 alluded briefly to Charles E. Frosst’s American roots without mentioning the following little-known, fascinating facts about Frosst’s American heritage:

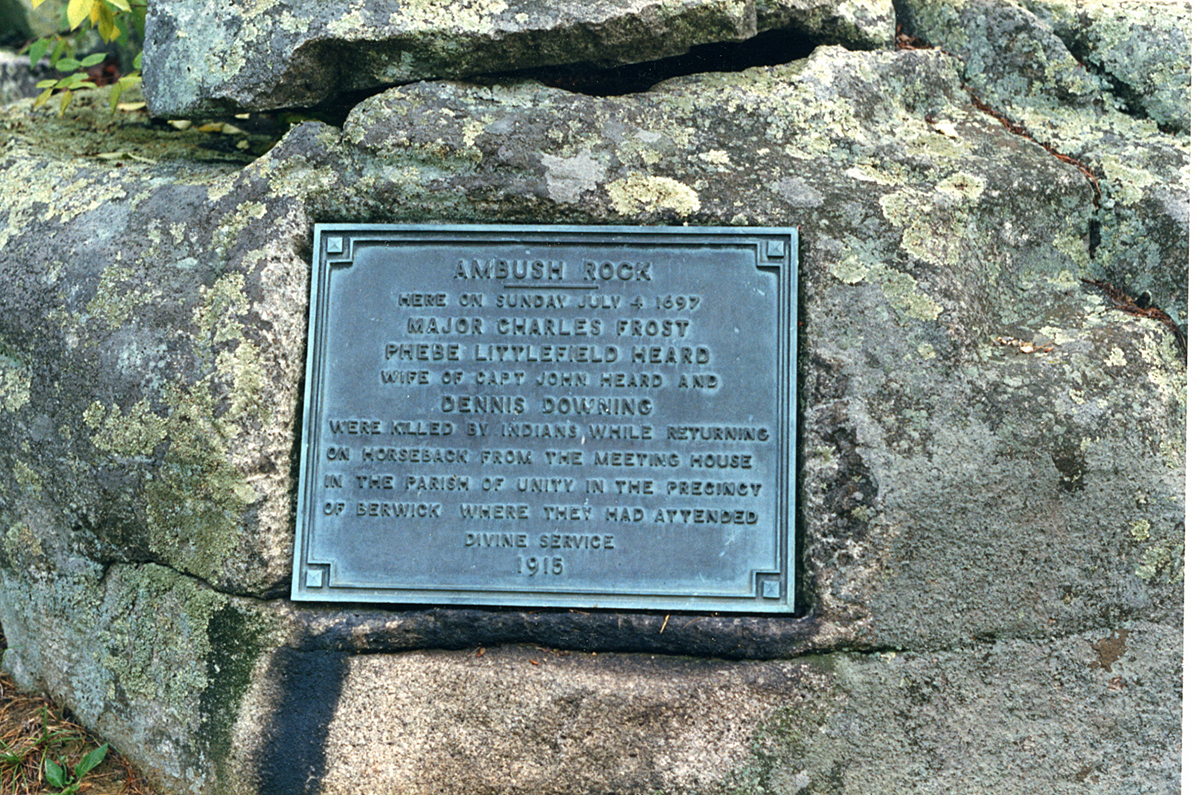

- His ancestors migrated to New England from Devon, England circa 1634, about 14 years after the Prilgrims arrived at Cape Cod aboard the Mayflower – at which time the American colonies were under English rule.

- Six generations prior to the birth of Charles E. Frosst, his forebear – Maj. Charles Frost* – was killed in an attack by natives in Kittery, Maine on his way home from church on Sunday, July 4, 1697. Maj. Charles Frost’s grave on a hilltop near his home is marked by a granite stone which is said to be the oldest gravestone in the state of Maine, according to ancestry.com. It lies next to a large boulder known to locals as ‘Ambush Rock’ because it marks the spot in Eliot, Maine where Frost fell victim to a surprise attack by natives.

- Maj. Charles Frost* IV (Charles E. Frosst’s great-grandfather) fought with Gen. George Washington in the American War of Independence waged between 1775 and 1783.

*[Editor’s Note: The family name was spelled with one ‘s’ in the 1600s and 1700s.] - Charles E. Frosst’s father was born in South Berwick, Maine and was named George Washington Frosst in honour of Gen. George Washington.

- In 1850 at age 23, George Washington Frosst moved to Richmond, Virginia in order to escape the frigid Maine winters. But in 1862, with the American Civil War raging, he was imprisoned for six months in Salisbury Prison in North Carolina on suspicion of being a Yankee sympathizer due to his northern roots.

- In 1900 at age 73, George Washington Frosst collaborated with author J. Dennis Robinson to write a memoir recounting how in 1863 he successfully planned his family’s escape from the Confederate capital of Richmond back to his birthplace in South Berwick, Maine. After the Civil War ended in 1865, he moved his family back to Virginia, where his son Charles E. Frosst was born on December 27, 1867.

Although the Frosst family has deep historical roots in America, Charles E. Frosst’s March 19, 1948 obituary in The Gazette emphasized that “his keen sense of business coupled with his pleasant personality soon made him hosts of friends throughout the [British] Dominion” as founder and chairman of what would become Canada’s leading R&D pharmaceutical company.

Frosst was unabashedly proud of his accomplishments since moving to Canada: he flew a large Union Jack flag above his St. Agathe country house in the Laurentian Mountains north of Montreal where he spent a lot of time after he retired in 1943. He left the company in the capable hands of his three sons although he remained chairman of the board until his death.

[Editor’s Note: The United Kingdom’s royal union flag, known as the Union Jack, was considered Canada’s principal flag until the Liberal government of Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson adopted the current Maple Leaf as Canada’s official flag in 1965. However, it should be noted that there were other Canadian flag versions known as the Red Ensign flown between Canadian Confederation in 1867 and the adoption of the Maple Leaf in 1965. The Canadian Red Ensign always depicted the Union Jack in the upper left corner with various shields in the lower right quadrant showing a provincial coat of arms surrounded by branches of maple, oak, or laurel, as well as beavers and crowns.]

Despite their love for Canada, it is interesting to note that neither Charles E. Frosst nor his wife, Stella, ever gave up their American citizenship – likely because there was no legal category for Canadian citizenship until the Canadian Citizenship Act came into force on January 1, 1947. All Canadians were considered to be British subjects and held British passports until that date – meaning the only option for the Frossts would have been to become British subjects. And that would have meant giving up their American citizenship because the U.S. did not allow for dual citizenship until 1967 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down most laws banning that practice.

A check of the Library and Archives Canada database shows no naturalization certificates were ever published in the Canada Gazette in the names of either Charles E. Frosst or his wife, Stella. A search of citizenship registration records at the Montreal Circuit Court database also fails to produce any references to the name Frosst.

The 1931 Census of Canada database lists the immigration status for both Charles Edward Frosst and his wife, Stella, as ‘al’ – the abbreviation for ‘alien’, meaning they were not listed as British subjects living in Canada. Had the couple applied for naturalization papers but had not yet reached the full status of British citizenship, their immigration status in the 1931 census would have been indicated by the letters ‘pa’ – the abbreviation for ‘papers’.

But when Frosst passed away on March 18, 1948, those who mourned his loss were focused on the contributions he had made to Canada through both his business and his personal life; not on his citizenship status.

In the obituary published on March 19, 1948, The Montreal Daily Star wrote that Frosst “lived to see his name at the head of an international organization, [and] his products recognized everywhere.” It went on to say: “Like so many other men who have made their mark in their chosen calling, he saw what he thought was an opportunity in a comparatively new and small field and seized it.” The newspaper noted that Frosst “gave generously to scholarships and bursaries which helped many a young student of small means.”

The funeral service was conducted at Westmount Baptist Church on Saturday, March 20, 1948. Among the mourners were Frosst’s wife, Stella, and her three sons who had joined their father’s pharmaceutical business and who also lived in Westmount: Eliot S. Frosst; John B. Frosst; and Charles E. Frosst Jr.

Also in attendance were his three daughters and their husbands: Mr. and Mrs. Colin W. Webster of Montreal; Mr. and Mrs. Dougall Cushing of Montreal; and Dr. and Mrs. J. M. Alexander of Charlotte, North Carolina. The Montreal Daily Star of March 22, 1948 also cited the presence of four of Frosst’s 16 grandchildren: grandsons Eliot B. Frosst; Lorne Webster; Charles E. Frosst III; and Alan C. Frosst.

The Montreal Daily Star reported that “scores of friends, relatives, and former business associates paid final tribute…to one of the city’s most prominent. businessmen.” The church choir sang two of Frosst’s favourite hymns: ‘Lead, Kindly Light’ and ‘Jesus, Lover of My Soul’.

In both life and death, the prominence of the Frosst family on the Montreal social scene was well documented in the daily press, including writes-ups about private dances they threw for friends and acquaintances at the toney Ritz Carlton and Mont Royal hotels in downtown Montreal.

When their daughter, Jean, married Montreal industrialist Colin Webster on December 1, 1927 in Westmount Baptist Church, it was a major event of the social season. Webster was the eldest brother of Howard Webster, the honorary chairman of The Globe and Mail newspaper in Toronto, and the son of Senator Lorne Webster whom he succeeded as president of the Canadian Import Co. Ltd. News of the marriage made the pages of newspapers in both Canada and the U.S. with the Richmond Times reporting on November 19, 1927 that the bride-to-be, Jean Frosst, had attended an exclusive all-girls junior college called Miss Bennett’s School in Millbrook, Duchess County, N.Y.

The wedding reception was held at the home of the bride’s parents at 17 Forden Avenue in Westmount with guests from across Canada and the U.S. in attendance. Their daughter’s wedding was one of many celebrations that Charles E. Frosst and his wife, Stella, held at their home over the years, including Christmas parties and their Golden Wedding Anniversary bash on June 5, 1945.

The 13-room, three-storey, stone-and-brick home, built in 1903 was bought by Charles E. Frosst on December 4, 1919, according to municipal land records. The Frosst family sold it for $18,000 in 1956, the year after their mother, Stella, died there “suddenly” on February 15, 1955 at age 84. The house was subsequently sold for $575,000 in July 1986 to Montreal businessman André Desmarais* and his wife, France Chrétien. Interestingly, the house sits just a few blocks from the Forden Crescent home where retired Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and his family lived between 1993 and 2015.

[Editor’s Note: André Desmarais is deputy chairman of Power Corporation, which is an international conglomerate with extensive holdings in energy and finance. Desmarais and his wife put the house on the market in 2015 for $4.5 million, according to the French-language TVA news network, but it was never sold.]

Following the patriarch’s death in March 1948, there was a renewed commitment by Frosst’s sons to producing the iconic annual Dingbat calendar with the usual 55,000 to 60,000 press run distributed annually to doctors, dentists, pharmacists, scientists, and hospitals across Canada. Besides the calendars, Charles E. Frosst & Co. published posters, coasters, and matchbooks – all sporting images of the beloved Dingbats.

Fortunately for Frosst’s sons, Lawrence Robb Batchelor – the third illustrator chosen by Charles E. Frosst to continue in the footsteps of artists Dudley Ward and Ross Wiggs had just started his Dingbat reign in 1947, one year before Frosst died.

But Batchelor’s passing on May 14, 1961 didn’t leave the Frosst sons much time to find a replacement to create the 1962 Dingbat calendar – given that conceptualizing an original, scientific scenario while trying to copy Dudley Ward’s original Dingbat style required great illustration skills and ample lead time.

Dingbat artist No. 4

The deep social and business connections of the Frosst family led them to a supremely gifted artist named Alexander Lithgow McLaren (1892-1978) whom they anointed as the fourth Dingbat illustrator to replace L. R. Batchelor.

Alex was born in Portugal in 1892 of Scottish parents, each of whose family name was McLaren. His father died when Alex was 8 years old, after which his mother took him back to her native Scotland. At a very young age, he already exhibited striking artistic talent studying at the Dundee School of Art where he was awarded first prize and first-class honours, according to ‘A Dictionary of Canadian Artists’ written by Colin S. MacDonald and published in 1979.

Arriving in Montreal to visit his brother in 1911 at age 19, he fell in love with the city and its culture, opting to study painting at École des Beaux Arts under famous landscape and portrait artist Edmond Dyonnet who had himself immigrated with his family to Montreal from his native France in 1875 when he was 16 years old.

Like Ross Wiggs, the second Dingbat artist, Alex McLaren – the fourth Dingbat artist – studied at the Art Association of Montreal under famous painter Maurice Cullen. Cullen is described in The Canadian Encyclopedia as “a major figure in Canadian art” whose “gift was that of a romantic: an ability to capture light and mood.” He has been dubbed the ‘Father of Canadian Impressionism’ because he was the first artist to adapt French Impressionism to Canadian climatic and geographic conditions.

Given their close proximity in age – Alex McLaren was just three years older than Ross Wiggs – it is likely that Wiggs and McLaren had befriended one another during their days studying under Maurice Cullen. It is almost certain that Wiggs was the personal connection who led the Frosst family to hire McLaren to replace L. R. Batchelor as the fourth Dingbat illustrator.

Another sign pointing to Ross Wiggs as the bridge to Alex McLaren is the fact that Wiggs continued to have a personal relationship with members of the Frosst family that went beyond his nine-year tenure as Charles E. Frosst’s Dingbat illustrator. For example, in 1947 Wiggs completed the architectural drawings for the St. Agathe country house of businessman Colin Webster whose marriage in 1927 to Charles E. Frosst’s daughter, Jean, was one of the highlights of the Montreal social season.

The presumed connection is further supported by a November 5, 1969 article published in French-language newspaper La Victoire des Deux-Montagnes which noted that McLaren “became friends with other excellent artists” at the studio of his art teacher Maurice Cullen.

Despite his impressive drawing talent, McLaren – like many artists – was forced to hold numerous jobs to supplement his artistic earnings, including work as an estimator, cashier, accountant, lithographer, freelance graphic designer, and assistant advertising manager at The Montreal Star.

Peter Kellock, McLaren’s grandson, said in a telephone interview with BestStory.ca on July 1, 2024 that his mother Joyce Kellock Boyer – herself a well-known Canadian artist – once told him that her dad “was a great artist but he had to take whatever work came his way in order to put bread and butter on the table.”

Peter Kellock told BestStory.ca that an artistic motherlode runs through his family emanating from his grandfather, Alex Maclaren, who gave art lessons to his daughter Joyce (Peter’s mom) when she was a young girl. Peter Kellock says: “For sure, my grandfather saw talent in my mom at a young age. I have a photo of the two of them sitting together drawing – with him showing her what to do.”

Joyce, who passed away at age 91 in 2017, worked in many mediums but seemed to prefer watercolours. She is best known for her paintings of children in different scenarios which became known as ‘The Kellock Kids’. Among the proud owners of her artwork are former Gov.-Gen. Roland Michener, Hockey Night in Canada commentator Ron Maclean, and UNICEF officials.

Grandson Peter Kellock recalls that when the family visited McLaren on Sunday afternoons at his small house in Lac des Deux Montagnes – 24 miles northwest (38 km) of Montreal – they would find him brush in hand at his easel. He enjoyed painting landscapes from photos he had taken on trips into the nearby countryside or on vacations to Cape Breton Island where he had family nearby. Both his mom and grandfather had a good sense of humour, Peter recalls. “Granddad wasn’t a laugh-out-loud kind of guy, but he liked a good joke.” Peter said, noting you have to have a sense of humour to draw Dingbats.

Peter adds: “When I found out what he was doing with the Dingbats, I remember looking at all the calendar illustrations he did. He even showed us some of the previous ones done by other artists.”

And as with all the Dingbat artists who preceded him, McLaren was a strong supporter of the Canadian fighting man – in his case through artwork; not by joining the military.

During the Second World War, Alex McLaren created outstanding fundraising posters for the Canadian armed forces under the ‘Victory Bonds’ branding. One in particular, the 1942 poster with the heading, ‘How about YOU?’ touched the hearts…and wallets of many Canadians in its quest for donations to support Canada’s war effort. The painting depicted a mustachioed, blue-eyed officer with the Royal Canadian Air Force wearing a side cap with a white muffler wrapped around his neck and staring intently ahead with a sombre expression.

The Ottawa Journal of October 30, 1942 published a letter signed by a reader in Williamsburg, Ontario with the initials H. T. D. The reader wrote that the poster by A. L. McLaren had made “a profound impression” on him reflecting the artist’s “personality, sympathy, and faith in the cause; God forbid that we fail to feel it and to respond as we should.”

The Ottawa Journal Editor replied to the reader that A. L. McLaren’s poster “has attracted much favourable attention” and that its strength was derived from “its simplicity, its virility – the strong face and burning eyes of an airman below the words, ‘How About YOU?’”

Dingbat artist No. 5

On November 9, 1978, McLaren died at age 86 in St. Eustache General Hospital about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Montreal. His passing left the final 14 years [1980–1993] of Frosst-branded, Dingbat calendars in the care of German-born artist Gunter Julius Scherrer (1928-2018) who immigrated to Canada with his wife, Inge, in the early 1960s.

As a young child, Gunter was a self-taught, artistic prodigy, according to his wife, Inge, who spoke by telephone with BestStory.ca on June 17, 2024. “He could draw anything when he was just 6 years old,” she said of her husband. “He had a lot of natural talent.”

Born in the small Rhine Valley town of Karlsruhe, Gunter was a young boy of 11 when the Second World War broke out in 1939. Although he did not lose immediate family in the Second World War, he had relatives who died in the First World War, Inge told BestStory.ca. “He hated war,” she said in reference to her late husband.

After the Second World War, Scherrer studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart, founded in 1761 and located about 50 miles (80 km) from his home town of Karlsruhe, which is considered a German cultural hub. He was good in all artistic mediums, especially realism: his drawings often look like photographs, especially bucolic scenes depicting water and snow.

An online search turns up paintings by Scherrer ranging from Canadian countryside landscapes to realistic paintings of Second World War tanks, military aircraft such as the German Stuka dive bomber and ships including the HMCS Halifax – the first Royal Canadian Navy corvette commissioned on November 26, 1941.

In the 1950s while in his 20s and still living in Germany, Scherrer did book illustrations for the Walt Disney Company in Germany and was in high demand as an illustrator for publishing houses that included a “big publisher” who was Inge’s husband at that time.

It seems that Inge immediately fell in love with both the art and the artist from Karlsruhe. She divorced her “big publisher” husband, Walter, to marry Gunter, whom she calls the “love of my life”. The fact that Gunter Scherrer looked like a movie star out of central casting à la James Bond likely added heat to the fire! When asked about her decision to divorce her first husband, Inge told BestStory.ca: “It was a good goodbye!”

With the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 fresh in their memories and with tensions increasing between the Soviet Union and the United States, Inge and Gunter worried that the Cold War could erupt into a hot, shooting war that might, once again, engulf Europe. “Let’s get out of here,” Inge says she told Gunter. “I’ve had enough of this.”

As fate would have it, an acquaintance named Lottie had an aunt living in Montreal. The aunt invited Gunter and Inge to stay with her until they got settled in Canada. ‘Alors, bonjour la belle province!’ Both Gunter and Inge became Canadian citizens shortly after immigrating to Canada in the 1960s.

The December 7, 1965 edition of The Gazette carried a paid announcement by Collyer Advertising Ltd. that Gunter Scherrer had been appointed to be executive art director in the agency’s Montreal office. A few years later, Gunter and Inge started their own ad agency.

The 1965 Collyer communiqué did not mention Scherrer’s multifaceted accomplishments as a fine artist who worked in multiple mediums including oil on canvas, watercolours, pastels, and ink, but it did say that he was the author of a book on aeronautical design and illustration. It was titled ‘How To Draw Aircraft and Rockets’.

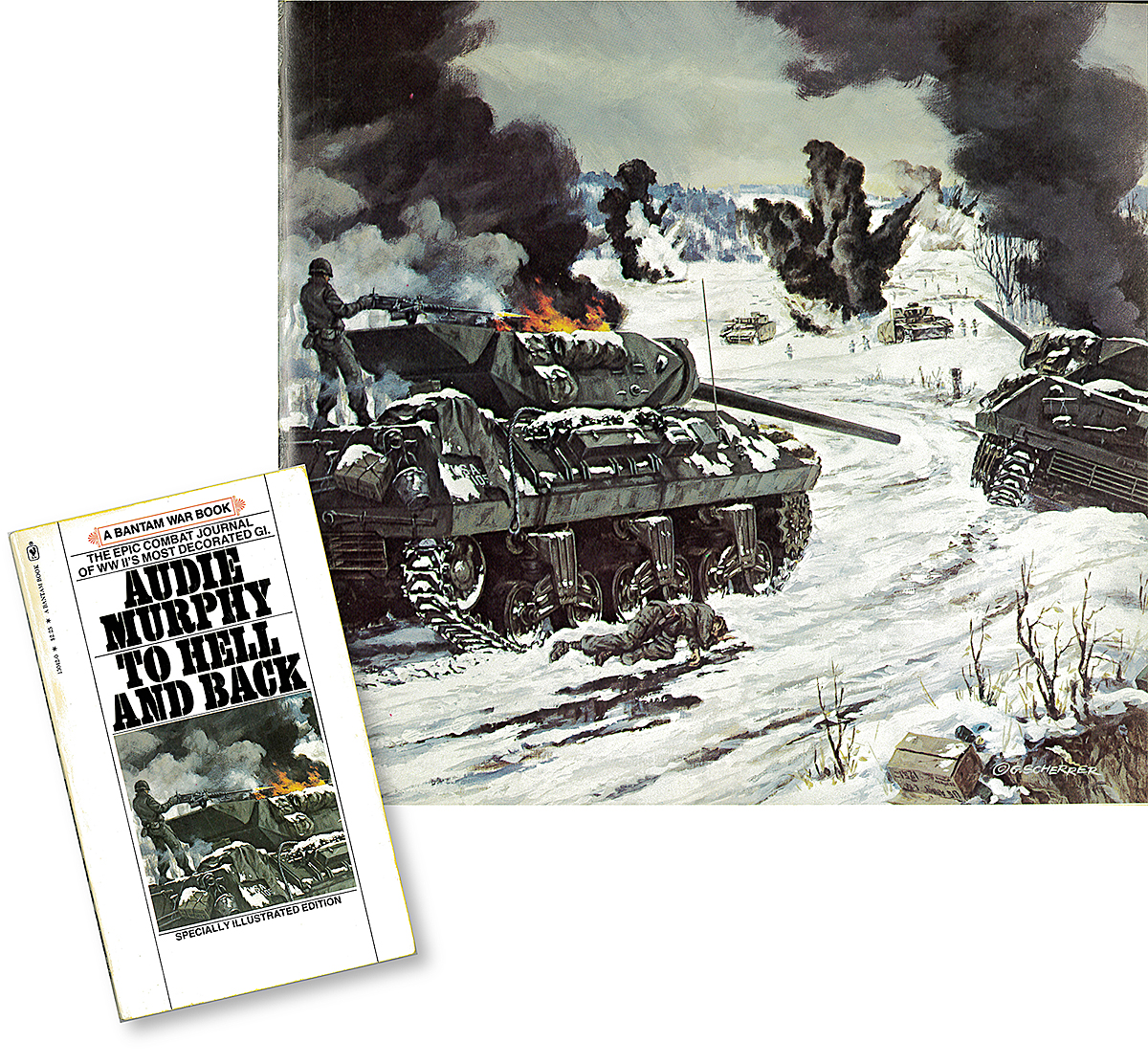

In fact, Gunter Scherrer’s extensive expertise about Second World War weaponry led to his being hired to illustrate ‘To Hell and Back’, the autobiography of Audie Murphy, America’s most decorated WW II soldier. The thrice-wounded Murphy was credited with 241 enemy kills, casualties, and captures fighting the German armed forces. After the war, Murphy enjoyed a long acting career in 40 movies, including the 1955 film version of his book ‘To Hell and Back’ in which the Texan played himself.

[Editor’s Note: Murphy died on May 28, 1971 when the chartered plane he was on crashed near the summit of a heavily wooded mountain 12 miles (19 km) northeast of Roanoke, Virginia.]

In 1979, Bantam Book republished Murphy’s autobiography which had originally come out 30 years earlier. Inge said that Bantam Books was aware of Gunter’s reputation and approached him to illustrate the 1979 version of the book with a cover drawing showing a soldier firing his machinegun atop a disabled tank.

The Bantam Book cover for Audie Murphy came one year after the 1978 death of the fourth Dingbat illustrator, Alex McLaren – meaning that the annual Frosst calendar was once again in need of a new artist. With a loyal following of tens of thousands of pharmacists, doctors, and dentists across Canada, the Dingbat calendar was a well-established cultural phenomenon affording a high profile to an illustrious list of illustrators dating back to the first 1915 calendar created by Dudley Ward.

Having lived in Montreal for 13 years by then, Gunter Scherrer was well aware of the artistic patina of the Dingbat calendar. Inge told BestStory.ca that “Gunter took his portfolio under his arm” and left for a meeting with the Merck Frosst executives who were entrusted with finding a new Dingbat illustrator. Apparently, they were impressed with Gunter’s artistic chops because Inge recalls he came back in high spirits a short time later and announced to her: “I’m hired to do everything.”

Gunter loved creating the artwork for the Dingbat calendars, Inge said. “It was fun for him, relaxing, He did it pretty effortlessly.”

Thus began the reign of the last Dingbat illustrator which lasted 14 years until a 1992 ruling by the Canadian Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association that such calendars with product advertising on them presented an unfair competitive advantage for Merck Frosst. The last Frosst-branded calendar appeared in 1993.

Like all the illustrators who preceded him, Scherrer was a multidimensional, serious artist recognized for his prodigious skills well beyond the realm of the Dingbat calendars.

For example, in the 1980s, Scherrer designed a series of colourful bird figurines manufactured in porcelain by German crafts company Goebel under the branding ‘Berdz’. Goebel, which still has an online presence featuring its product lines, was founded in 1871 in the village of Rödental in northern Bavaria. Scherrer-designed porcelain ‘Berdz’ are still traded on eBay.

It’s all about humour!

The high profile of Dingbats in Canadian pharmaceutical and medical circles created pressure for the artists to create different, high-quality illustrations year in and year out – always in the stylistic mold of Dingbat originator Dudley Ward.

Dudley Ward’s Dingbat calendars can be found in the National Gallery of Canada and in the Art Gallery of Ontario. Surprisingly, the Museum of Health Care in Kingston, Ontario has none of his or Ross Wiggs’ calendars in its collection, according to Shaelyn Ryan, who worked as a “Collections Technician” at the museum from 2021 until 2023. However, the museum does have examples of Dingbat calendars done by L. R. Batchelor, Alex McLaren, and Gunter Scherrer.

All the Dingbat illustrators seemed to share typical artistic personality traits: soulful insecurity, engrained humility, rebellious independence, and, oh yes, a healthy dollop of humour. Who could resist laughing at the antics of those funny little Dingbats throwing themselves with reckless abandon into crazy scientific quandaries?